During the late 2000s, the idea that telecoms services should be accessible to the widest number of people at affordable prices started to take root in Africa. The mechanism designed to ensure this goal would become a reality was the Universal Service Fund (USF). By 2013, Africa had over 20 USFs and most recent data indicates that of the 54 countries on the continent, 51 have either introduced or are in the process of introducing USF programs. Now that a decade of USF activity has passed – it’s fair to take stock and try to assess how impactful these programs have been and continue to be presently…

A GSMA survey and report on Universal Service Fund activity in Africa informs most of our coverage. The survey assessed 40 (of Africa’s 51) countries with USF programs in order to better understand how the funds operate, where the majority of their money comes from, the progress being made in and out of telecoms along with the challenges USFs are facing thus far.

The scope of the problem being solved by Universal Service Funds

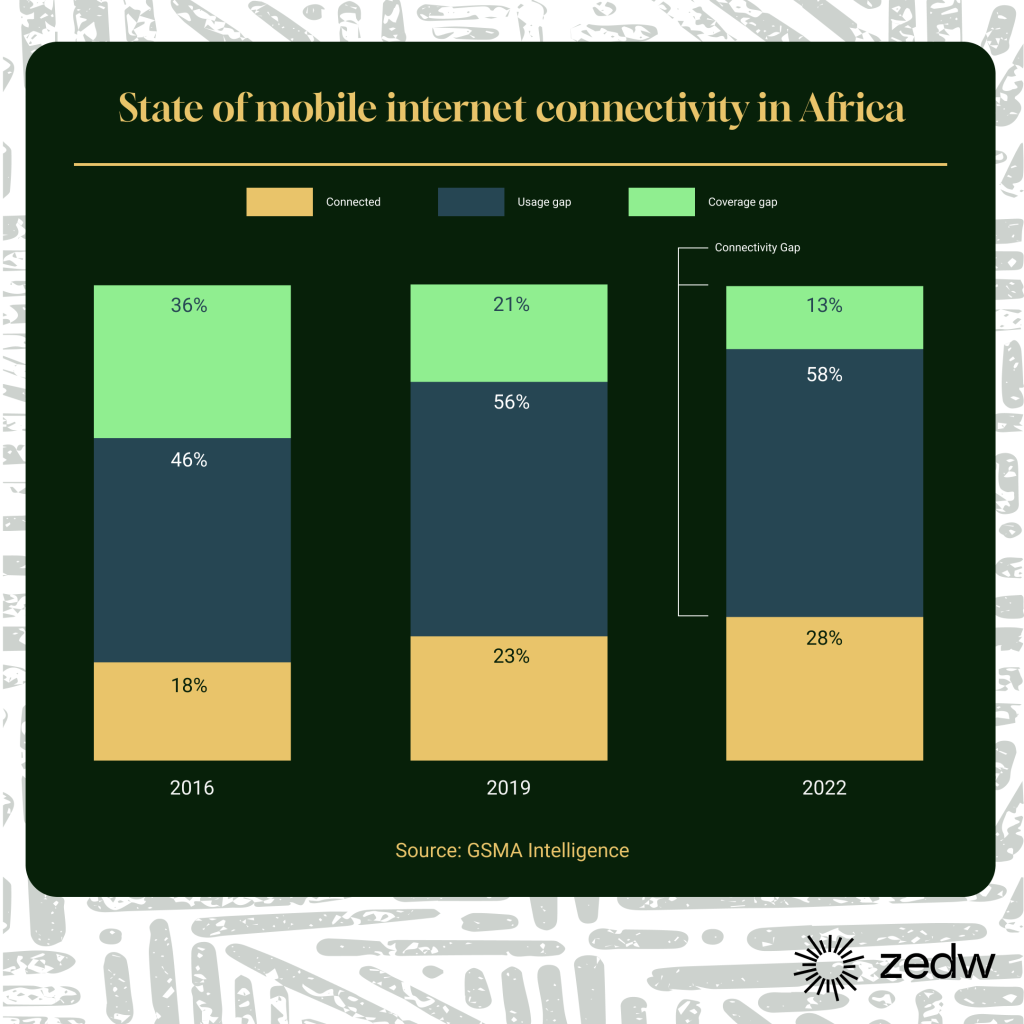

In the context of Africa, the problem to be solved was (and still is) significant. Presently, the continent still has the widest coverage gap of any region globally and at the end of 2022 – 72% of people in Africa still did not have access to mobile internet. GSMA defines the unconnected in two ways; 1) those who live outside of areas covered by mobile broadband networks (the coverage gap) and 2) those who live within areas covered by mobile broadband networks but do not yet subscribe to mobile broadband services (the usage gap).

Service provider and USF efforts have meant that the coverage gap has been closing – from 56% in 2012, the coverage gap went down to 13% at the end of 2022. Presently, an estimated 200 million people live in areas not covered by a mobile broadband network.

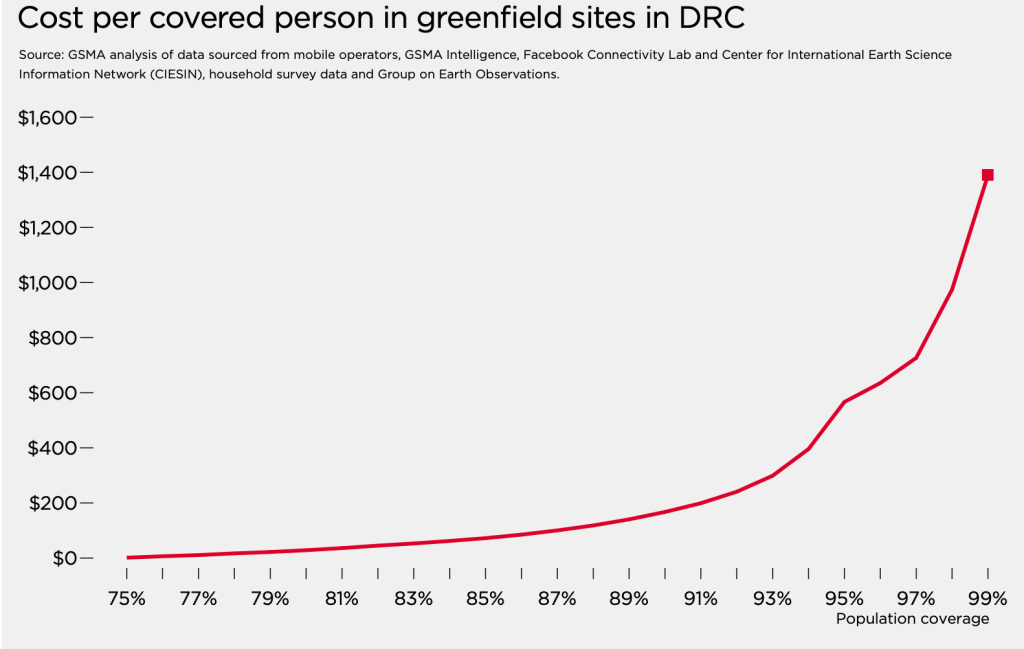

When it comes to coverage gaps it’s important to keep in mind that 100% coverage is unlikely and within the SADC region this can be illustrated by the DRC which has 75% and 54% coverage for 2G and mobile broadband networks respectively. That coverage has been achieved by building out 6,000 mobile sites and increasing coverage would require increasing the number of sites as follows:

- to move from 75% to 80% coverage requires another approximately 150 sites.

- to move from 90% to 95% coverage, 5,700 new mobile sites are needed.

- to move from 98% to 99% coverage, more than 2,000 sites would be needed.

“While it is technically possible to achieve universal coverage with existing mobile technologies, at a certain point the additional investment needed becomes an order of magnitude higher. These are areas that are remote and sparsely populated, with some sites covering no more than a few hundred people. Expanding coverage to these locations will therefore be extremely challenging using existing technologies, due to a combination of low population density and high costs. Providing coverage in a sustainable manner will likely require new innovations.”

GSMA| Universal service funds in Africa Policy reforms to enhance effectiveness report

In essence, to move from 75%-99% coverage would require more sites (7,950) than it took to move from 0-75% coverage. The move would also cost way more as GSMA claims that the cost-per-person covered to move from 75-76% coverage would be $7 but to $600 at 95% coverage.

This in part explains the internet experiments like internet balloons presented by Alphabet’s (Google’s parent company) or Starlink which is growing in popularity having added 500,000 users in the last four months. These projects are meant to be cost-effective ways to ensure the coverage gap is breached.

Policy reforms have been highlighted as potentially being able to help bridge the coverage gap or at least reduce the cost of bridging the coverage gap. USF subsidies in this regard would be to ensure more people are connected whilst saving millions of dollars…

Amount of investment needed to bridge the coverage gap:

| Expected mobile broadband without additional investment by 2030 | Expected coverage with additional investment | Investment gap (no policy reform), $ mn | Investment gap (with policy reform), $ mn | Coverage with 40% mobile broadband adoption | |

| DRC | 82% | 98% | $963 | $864 | 96% |

| Mozambique | 87% | 98% | $144 | $124 | 94% |

| Tanzania | 93% | 99% | $213 | $185 | 97% |

| Zambia | 89% | 99% | $57 | $54 | 97% |

The causes of usage gaps are more multifaceted and vary from country to country but in most cases, the following factors have been outlined as causes;

- a lack of access to affordable smart devices,

- lack of relevant digital services,

- low levels of digital skills,

- and (increasingly) online safety and security concerns.

These are, in a nutshell, the primary problems USFs are meant to be helping address but as we’ll see, the claimed efforts go way beyond making broadband accessible.

Where does the money come from?

With available data suggesting that between 2018-2022, US$1.5bn was contributed to USF funds in Africa this begs the question – who contributes? USFs are primarily funded by telecom service providers through levies on their revenues and licence fees. In a few countries like Botswana and Tanzania, non-telecoms service providers (broadcasters, post and courier operators, and licensed online content providers) also contribute to USF but GSMA claims they do so at a reduced rate compared to telecoms companies.

“…in Tanzania, the parliament can appropriate funds to the USF; in Eswatini, funds from a surplus declared by the NRA can be channelled to the USF; and in Ghana the law allows for donors such as the World Bank, ITU and other development agencies to provide grants and loans to support connectivity programmes.”

GSMA| Universal service funds in Africa Policy reforms to enhance effectiveness report

Besides fees collected from telecom licence holders, several funding sources support the Universal Service Fund (USF) in some countries. These include direct government contributions, revenue from spectrum auctions, any surplus funds identified by the National Regulatory Authority (NRA), charitable donations, and grants or loans from international organisations like the World Bank.

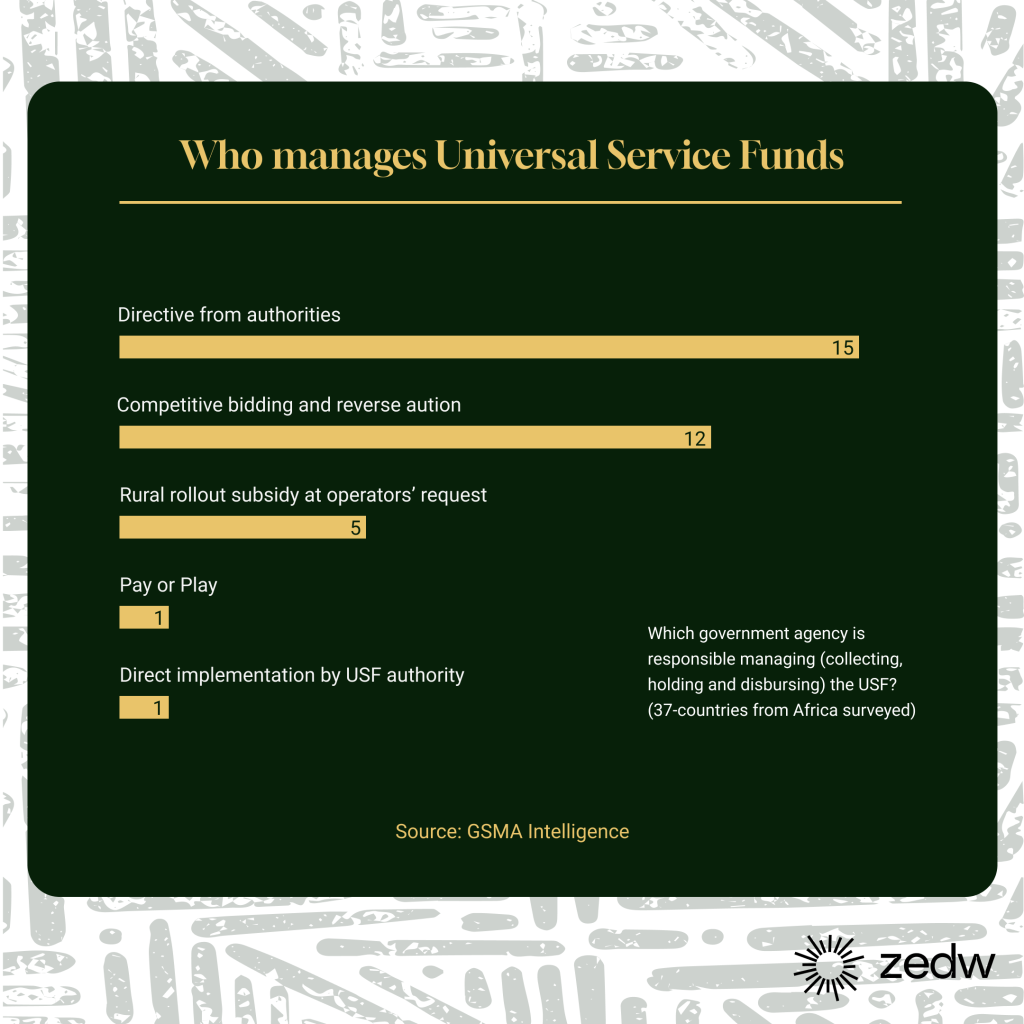

USFs tend to be managed by government agencies – the majority of which are managed within the country’s telecommunications national regulatory authorities (NRA). A survey conducted by GSMA containing 37 countries noted that 70% had service funds housed in the NRA.

Beyond this popular arrangement, there are alternative ways the USFs are managed on the continent including the creation of USF agencies, government ministries taking charge and even hybrid approaches. Here are a few examples;

- the Uganda Communications Universal Service and Access Fund (UCUSAF) is administered by the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), which provides technical and administrative support for the fund to lower its administrative costs;

- Ghana Investment Fund for Electronic Communications (GIFEC) and Côte d’Ivoire’s Agence Nationale du Service Universel des Télécommunications (ANSUT) are standalone USF agencies that manage funds in those countries;

- In Senegal, a department of the Ministry of Finance and Budget, is responsible for collecting and holding the fees, while the Coordination and Management Unit – under the Ministry of Communication, Telecommunications and Digital Economy – is responsible for disbursement.

- In Cameroon, the NRA collects the USF fees, which must be held by the Central Bank, while the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications authorises disbursements.

Funding extends beyond the obvious…

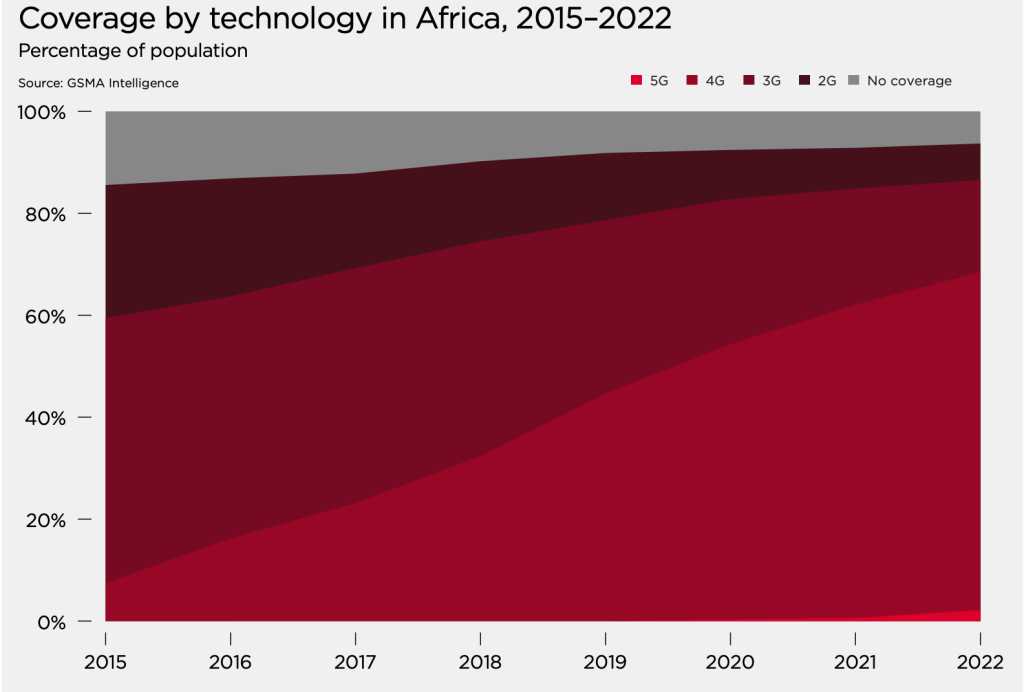

Naturally, the primary use of available funds has been infrastructure projects as the priority for the better part of the last decade was to ensure that the infrastructure enabled internet access. In this regard, most of the funds have been prioritised for broadband connectivity (3G/4G particularly). It appears that fixed connectivity (e.g. fibre) has been neglected largely because of cost and complexity.

In Zimbabwe, the telecoms regulator POTRAZ revealed that they had distributed 13,339 computers to 903 schools in addition to connecting 43 schools to the internet.

Outside of connectivity, other initiatives have been taken on including;

- Connectivity to schools/hospitals;

- Digital skills programs;

- Device subsidies;

- Service plan subsidies.

Morocco is an interesting case study as they are one of the few countries using USF funds to subsidise the cost of data and SMS. In Morocco, the USF has been used to zero-rate access to certain services and websites, such as SMS for vaccination appointments and websites for education.

Sometimes though the funds collected are not put to use. Between USF reporting 14 countries during 2015-2017, had US$176.6mn USF funds collected but not put to use. Alliance for Afforadable Internet claimed this amount could have provided a 75% subsidy for mobile internet access for six million women for half year and bridging the gap between men and women using the internet in Africa by 15% at the time… An example of this failure to put funds to use is Swaziland. A report on utilisation and management of USFs within the SADC region by Communications Regulators’ Association of Southern Africa CRASA in 2009 showed that Swaziland had collected $38mn in USF fees since 1990 but had only started disbursing them in 2001 and had only disbursed $6mn (15.8%). One of the recommendations from CRASA in that study was to urge countries collecting the funds to “expedite the disbursement of the collected funds to the projects in line with specified guidelines.”

The access to information problem

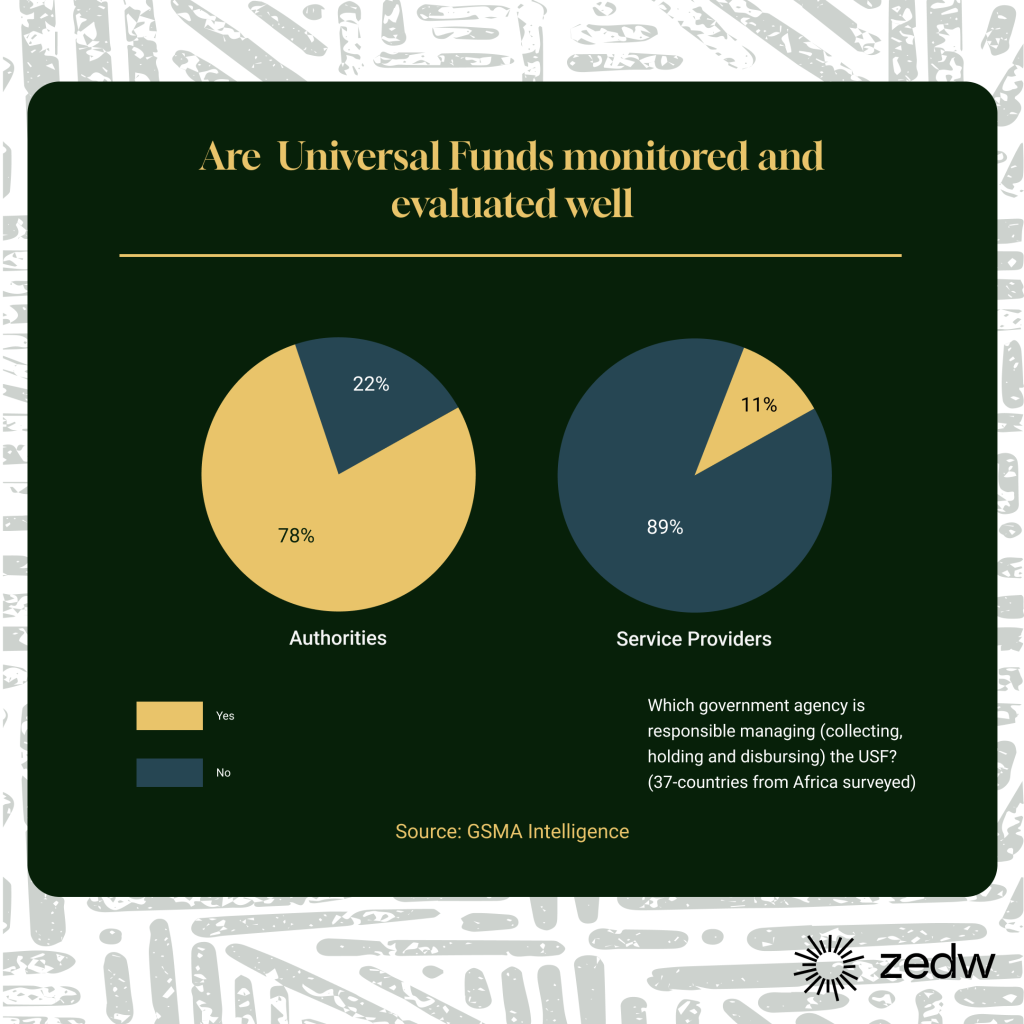

The primary target of the USFs though has always been to ensure that internet connectivity improves and, in that regard, – you could argue the closing of the coverage gap signals a success. What makes that statement hard to back is that – it’s quite difficult to determine just how much of that growth is attributable to the USFs and that is largely the fault due to the failure of USF managers to report on progress.

Across the continent – it’s hard to find consistent reporting on the progress or activities of USFs and telecoms service providers have long felt that the programs aren’t that effective. Public officers believe that there are monitoring mechanisms to assess the performance of USFs but the service providers involved overwhelmingly believe that isn’t the case. A4AI revealed in 2017 that only 23 countries in Africa (42.6%) had reports on USAF activities.

“This study found that less than a third of countries in the region publish detailed reports, including funds collected, expenditure and balance, on a periodic basis. In many instances, the most recently published report dates back several years, indicating underperformance or inadequate monitoring and evaluation.”

GSMA| Universal service funds in Africa Policy reforms to enhance effectiveness report

Challenges the Universal Service Funds need to address going forward

| Challenge | Detail |

| Dormancy | Although there is a general lack of public disclosure of funds collected and disbursed, the total unused amount held by 12 USF authorities that responded to the relevant question in the survey was $265 million. This represents more than half the amount collected in these countries over the last five years. |

| Regulatory flexibility | While the legal framework of USFs provides certainty on key elements, such as governance and implementation, in many cases it also raises questions around flexibility (or lack of it) to accommodate the continuous evolution of the telecoms sector. For example, USFs may not yet appreciate the growing shift from voice to data and the investment requirements of mobile internet networks. |

| Stakeholder consultation | Service providers play a central role in the performance of USFs, as both contributors and executors. However, the majority of USF authorities do not sufficiently consult with them or offer visibility of the management of funds and the rationale behind implementation decisions. There are some best-practice examples in the region, such as Ghana, where service providers are represented on the board of GIFEC. |

| Reallocation of funds | There are concerns around the reallocation or misappropriation of funds on activities not remotely related to connectivity. The lack of regular reporting and performance evaluation fuels these concerns. Of the 10 USF authorities that indicated that all funds collected have been spent, less than half publish performance reports on a regular basis. |

| Independence | Political intervention or interference from other government agencies inevitably affects the performance of USFs. This appears to be a common feature in Africa and one exacerbated by governance scenarios where the Universal Service Fund authority does not function as a separate, independent unit. Lack of independence of the Universal Service Funds authority can affect the performance of the fund in terms of delays in budget approval, redirection of funds to other uses, and excessive bureaucracy for project approvals, resulting in redundant administrative costs that reduce the amount available for implementation. |

| Institutional capacity | USFs require skilled personnel throughout the entire project lifecycle, from planning and design to implementation and performance evaluation. Many USFs in Africa lack personnel with the required legal, technical and project management expertise to execute major projects, with ongoing issues around high staff turnover, particularly for leadership and technical roles, poor motivation among existing staff, and inadequate skills capacity for the tasks required. |

| Supporting infrastructure | Lack of supporting infrastructure – in the form of poor road networks, inadequate security and lack of grid electricity – is often not factored into the implementation of USF projects.This can lead to poorly executed or abandoned projects. |

| Operating expenses | Service providers face ongoing operating costs to maintain networks. These can be expensive, given the lack of supporting infrastructure, and uneconomical, given the lack of market potential in rural areas. If a workable solution is not found to the opex challenge, the appetite for coverage expansion in uneconomical areas – even with USF funding – will remain limited. |

| Reliable data | USFs in the region often lack relevant, reliable data on vital indicators, including coverage gaps, population density and mobility, and social and economic profiles, to design and analyse the sustainability of network projects. Poor planning leads to execution problems, a mismatch between allocated funds and project requirements, and conflicts between authorities and service providers. |

| Transparency | Most countries in this study do not have a formal public reporting process for USFs.This makes it difficult for contributors and other stakeholders to ascertain details of the management of funds and implementation of projects. The perceived transparency issue has the potential to create mistrust among stakeholders, to the detriment of the overall objectives of the USF. |

| Clear objectives | Many USF frameworks were designed at a time when the connectivity landscape looked different. As such, some objectives sound vague and contradictory when interpreted today. For example, the definition of underserved areas qualifying for USF. |

“Even the most conservative estimates of the amount collected since inception would put the figure at more than $5 billion. However, there has not been a comprehensive study of the overall impact of the US since inception in any country in the region. The lack of empirical evidence on the impact of USs to date can limit the ability of authorities to make informed decisions on the future of USFs.”

GSMA Intelligence

Telecom service providers have long been dismissive of USF efforts as inconsequential – in Zimbabwe, Econet called for the scrapping of the USF entirely back in 2012 noting that the telecom service providers themselves were laying out infrastructure in remote areas. In 2014, the company again questioned the USF’s fairness as they felt they were the only ones contributing whilst their local competitors were being let off the hook.

It’s hard to share such a dismissive tone given that the USF is meant to ensure connectivity for all, but the fact that Universal Service Funds in Africa are entering their second or third decade and it’s still hard to concretely quantify their impact on connectivity justifies the service providers’ hardline stance. Until there is consistent reporting proving