The 2008 Zambia SME policy is a quiet revolution on how to formalize the informal sector. The deliberate and patient policy has garnered measurable results through the relatively honest reporting from the Zambian Government’s Agencies.

Small to Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are the backbone of the global economy and their importance is underscored by the fact that they represent 90% of businesses and more than 50% of employment worldwide according to The World Bank. With projections of an estimated 600 million jobs by 2030, SMEs are a hard segment of the market to ignore and that is why many governments have them as a high-priority policy point.

However, it is more than plain sailing, particularly in Africa. The rate of informality of businesses is near 83% in Africa as a whole, and 85% in Sub-Saharan Africa according to the International Labour Organisation.

This puts the youngest continent on the planet (with a median age of 20 and 60% of the population under the age of 25) in a predicament. Many who are coming to an age where they are seeking employment are left sometimes with few options because, whether they hold some qualification or not, the job market is tough, to say the least.

Furthermore, that generation of job seekers are, without an avenue into the small pool of formal businesses, left with little option but to find employment where they can and that in most cases leads to the informal sector.

The informal sector is the bane of African governments

African governments are, by this trajectory, losing valuable revenue that they need to build their respective economies, sustainably reduce market externalities, regulate trade, achieve tax justice and, build state accountability and responsiveness.

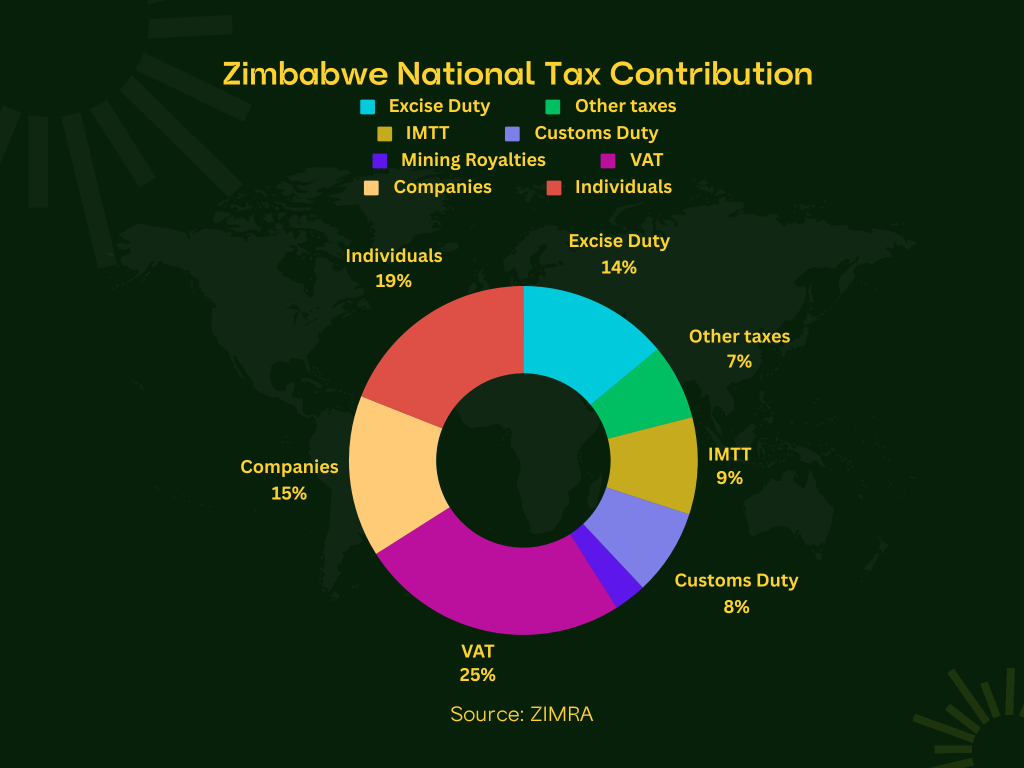

At present, there has been a patchwork of solutions that have had varying degrees of success. If we are to look at the perennial edge case, Zimbabwe, the motive has been to capture taxes through means that impact both those who are compliant and the informal… The Intermediary Money Transfer Tax (IMTT) was, in my opinion, an abdication of responsibility when it came to formalising the formal sector.

What it achieved was to make basic goods and commodities a little more expensive and leave the entire population at the whims of how advanced their financial services provider’s systems were at remitting the transaction-based tax to the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZIMRA). There have been several cases of banks making announcements telling their customers that they need to settle a years-long backlog of unpaid taxes to the tax authority.

On the other hand, it did solve a short-term problem of getting cash into the government coffers.

A share of 9% of the ZWL$1,992.19 Billion (US$153 million at the prevailing rate) is money that the Zimbabwean government wouldn’t have gotten had they not instituted the IMMT. That’s not to say it solved the problem… It did the opposite and exacerbated the issue. All we need to do is look at informal traders who moved away from transacting through digital and local currency-based channels and instead opted for cash (predominantly the United States Dollar) which is far harder to track and tax.

Why Zimbabwe is important, in this case, is because just over its northern border there has been something quite different happening not just recently, but over decades…

Zambia went the long way around with SMEs and the informal sector

Shortcuts are great if they work… Across the Zambezi a different approach was taken by Zambia in 2009, the country launched an SME Policy which when reading it, gives a mixture of “we are at wit’s end” or an honest admission that things are not working.

Policy documents are often ladened with ambiguous statements and grandiose claims but the Foreward of Zambia 2008 document on SMEs started on a very sober note.

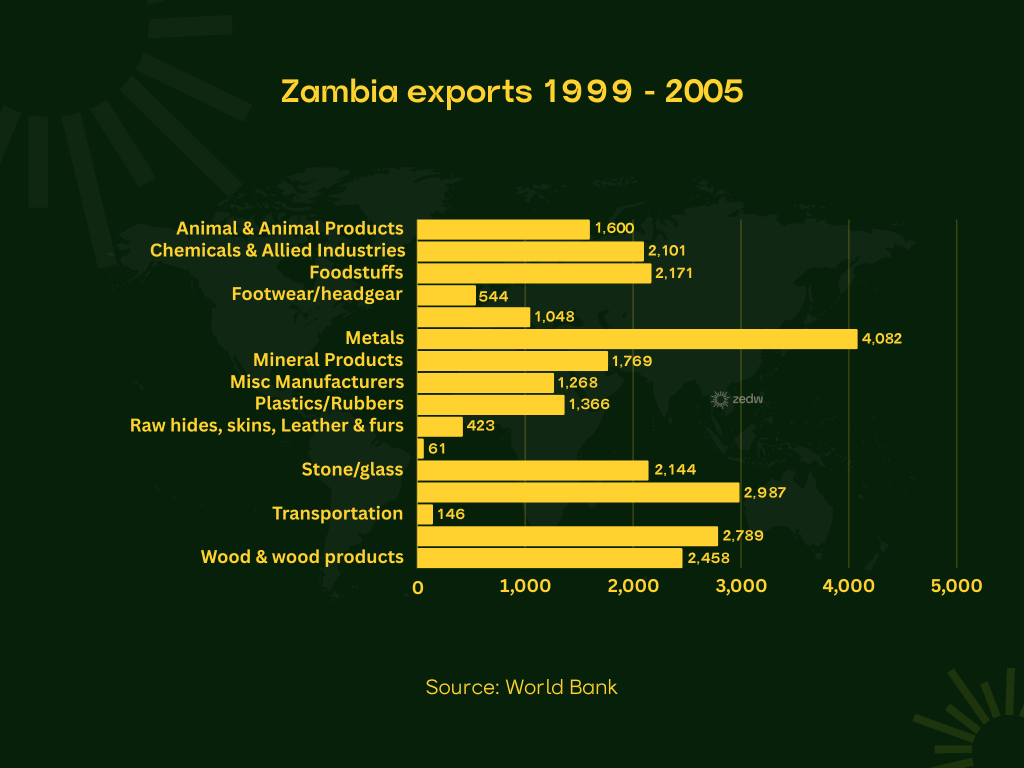

“Zambia recognises the need to diversify her economy and reduce overdependency on mining exports. The preferred strategy was production of non-traditional export products and creation of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises…”

Zambia SME Policy 2009

Copper and its products made up 70% of all exports in 2007.

The history of this shift started in 1991 with the election of the government led by Frederick Chiluba which, with aid from the World Bank, began an ambitious plan of reforming the economy. The key steps to this were:

- Repealing the Exchange Control Act

- Removal of price controls and subsidies

- Removal of import licence requirements

- Liberalisation of exchange rates

“As a result of these stabilization measures, the macroeconomic environment was brought under control. Inflation dropped to 54.6 per cent in 1994, and from 1994 to 1997, the annual rate of inflation declined from 54.6 per cent to 24.8 per cent. In the first quarter of 1998 inflation stood at 18 per cent.” – Growing Micro and Small Business Enterprises in LDCs (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development)

The consequence of this development was hyper privitization which led to the increasing number of traders in the informal sector. This was also worsened by the closure of parastatals, leading many who were previously employed to seek work where they could. What was equally worrying was that those individuals were predominantly in retail and not areas of production.

Organisations without Policy for Informal SMEs in Zambia

In the 90s, when all these changes were being made, there was a slew of organisations and boards that were formed to handle the issue of SMEs. It started with the launch of the Small Industries Development Organisation (SIDO) which was later replaced by the Small Enterprises Development Board (SEDB) in 1996. What both entities sought to do was cater for the financing needs of SMEs under the Small Enterprises Development (SED) Act.

The function of this entity was to provide support for Zambians who were starting new businesses. It dovetailed with other institutions, namely the Zambia Development Agency (ZDA), the Zambia Investment Centre (ZIC), Zambia Privatisation Agency (ZPA), the Export Board of Zambia (EBZ), and Zambia Export Processing Zones Authority (ZEPZA).

The SED Act came with some incentives, chief among them being the exemption of income tax for the first five years. The ability of a manufacturing company to operate without the requisite licence and expenditure on training staff that specialise in SMEs is regarded as tax-deductible.

Moreover, there were further exemptions which included, trade licensing for an organisation registered under the SED Act, no tax paid on income accrued from rentals on buildings or premises that were housing SMEs, and paying rates on factory premises among others.

Although progress was being made, there were still some issues with the structures that had been set up. For starters, there was no definition of a Medium Enterprise. In 1996, the SEDB only had a definition for a micro-enterprise:

- Total investments not exceeding 10 million kwacha (excluding land and buildings);

- An annual turnover which does not exceed 20 million kwacha; and

- Employs up to 10 persons.

- Has total investments not exceeding (excluding land and buildings):

- 50 million kwacha in plant and machinery for manufacturing and processing enterprises;

- 10 million kwacha in the case of trading and service enterprises;

- Has an annual turnover not exceeding 80 million kwacha; and

- Employs up to 30 people.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) noted, in the report titled “Growing Micro and Small Business Enterprises in LDCs“, that many of the small enterprises exceeded the stipulated amount for revenue. Moreover, there were no checks, at the time, to see which “small enterprises” had exceeded the preset threshold for Small Enterprises by the SEDB. This meant that there was no way that SEBD would be able to know which enterprises were no longer able to receive the incentives in the SED Act.

Without a policy to be the backbone of the change that was happening in the Zambian Private Sector, it was going to be difficult to address the morphing landscape.

“In the absence of an MSME Policy, development of the sector and coordination of development interventions has remained a major challenge in this country. It is anticipated that the challenges facing the MSME sector shall be resolved through strengthening of the capacity of MSE Division of the Zambia Development Agency, establishment of an independent National Council for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise Development and the implementation of the provisions of the MSME Policy.” –

Felix Mutati, MINISTER OF COMMERCE, TRADE AND INDUSTRY

How the first SME policy in Zambia sought to address the problems

What came quickly in the Zambia SME Policy of 2008 was that they wanted to gain situational awareness. This meant doing the hard work of understanding the landscape as it stood and the numbers were pretty dire.

90% of the MSME sector was informal. A survey from 1996 gave those who drafted the policy a baseline which showed that the sectors dominated with a workforce across most SMEs of less than 10 employees. Additionally, 52% of SMEs were rural-based within the entirety of the sector. 10% accounted for those operating in “Services”, 4% were in Manufacturing while trading made up 41%.

The first thing that needed to be done was outlining clearer definitions of the range of businesses that were termed SMEs and the thresholds of:

- Total fixed Investments

- Sales Turnover

- Number of employees.

- Legal status

Revision of the definitions of what SMEs were in Zambia according to the 2008 Policy were:

| Micro Enterprises | Small Enterprise | Medium Enterprise | Informal Enterprise |

| A micro-enterprise shall be any business enterprise registered with the Registrar of Companies; i) Whose total investment excluding land and buildings shall be up to Eighty Million Kwacha (K80,000,000) .ii) Whose annual turnover shall be up to One hundred and Fifty Million Kwacha (K150,000,000) .iii) Employing up to ten (10) persons | A small enterprise shall be any business enterprise registered with the Registrar of Companies; i) Whose total investment, excluding land and building- In the case of manufacturing and processing enterprises, shall be between Eighty Million and Two Hundred Million Kwacha (K80,000,000 – K200, 000,000) in plant and machinery;- In the case of trading and service-providing enterprises shall be up to One Hundred and Million (K150,000, 000) Kwacha. ii) Whose annual turnover shall be between One Hundred and Fifty Million and Two Hundred and Fifty Million (K151,000- K300,000,000) Kwacha. iii) Employing between eleven and forty-nine (11- 50) persons. | A medium enterprise shall be any business enterprise larger than a small enterprise registered with the Registrar of Companies; i) Whose total investment, excluding land and building;- In the case of manufacturing and processing enterprises, shall be between Two Hundred Million and Five Hundred Million (K201,000,000 –K500, 000, 000) Kwacha in plant and machinery,- In the case of trading and service providing shall be between One Hundred and Fifty-One Million and three Hundred Mullion (K151, 000,000 –K300,000,000) Kwacha. ii) Whose annual turnover shall be between Three Hundred Million and eight Hundred Million) (K300,000 ,000 – K800,000,00). iii) Employing between Fifty One and One Hundred (51 -100) persons | An informal enterprise shall be any business enterprise not registered with the Registrar of Companies; i) Whose total investments excluding Land and Building shall be up to Fifty Million (K50, 000,000) Kwacha. ii) Employing less than Ten (10) persons |

In the policy, some key strategies and statements were going to guide the implementation of the SME Policy in Zambia. Those focus areas were segmented into three pillars the first being capacity, which looked to address entrepreneurship development as well as innovation and technological capacity of SMEs.

Zambia’s SME Policy stated that the culture of entrepreneurship was not well developed in the country. Whatever metric they were using, showed that there were low levels of entrepreneurial ability with many of the SMEs not going beyond the growth phase. The remedy to this was to

“Inculcate a culture of entrepreneurship among citizens and facilitate development of entrepreneurship and enterprise management skills critical to the growth of MSMEs.”

2009 SME Policy Zambia.

At the time this was going to be executed through the Ministry of Education and Technical Vocational and Training (TEVETA) to harness and grow those entrepreneurial skills.

The second pillar was around access, giving the SME sector in Zambia access to market opportunities, business development services, appropriate financing and operating premises and business infrastructure.

Research, trade agreements, exhibitions, and training in various skills including marketing and export readiness was going to be how the second pillar was going to be implemented.

Lastly, the operating environment was the final pillar which sought economic development, representation of SME interests and addressing issues of gender and HIV/AIDS.

Government lobbying via SME trade associations and other interest groups to foster gender equality and lessen discrimination against people of various abilities and capacities was how the third pillar was to be executed.

The implementation of all of these moving parts was outgoing to involve:

- The Ministry of Commerce and Trade – leading the Government of Zambia in developing SMEs

- Enterprise Development Council – would build national consensus on matters related to SMEs

- Zambia Development Agency (SME Division) – would focus on operationalising government policy through programmes.

- MSME Development Organisations – would be intermediaries involved in delivering the support SMEs need. They consisted of NGOs, Donor Projects, Private Sector Organisations and MSME Umbrella Organisations.

- SMEs and their Associations: They would be responsible for mobilising members in various parts of the country and identifying beneficiaries of SMEs needing support in Zambia.

- Interministerial Cooperation and COllaboration – The Ministry of Trade and Industry would work with other ministries and government agencies to support the efforts of SMEs.

Measuring the success of the 2008 Zambia SME Policy

Understanding what has been going on with SMEs in Zambia from the 2008 SME Policy onward is a complex of several metrics that have been reported by different government agencies. For this article, the key indicators we will be looking at are the following:

- Overview picture of the SME space in Zambia

- Formalisation of SMEs (Business Registrations)

- Taxation (the number of SMEs that the Zambian Revenue Authority registers)

I think these metrics reflect the work on the ground from the policy that was set out in 2008.

Overview

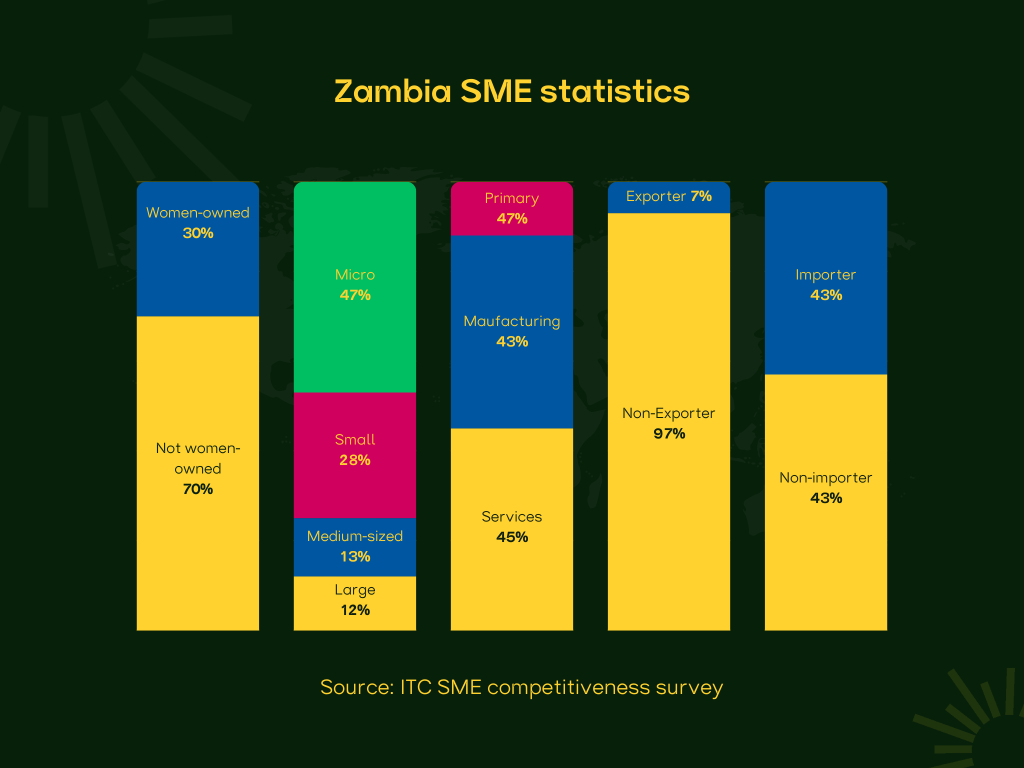

The International Trade Centre (ITC) surveyed the competitiveness of SMEs in Zambia. The general outlook of the findings is that the disparity between mineral and the export potential of SMEs is still not at the levels that show a pronounced diversification of the economy with 93% of SMEs in Zambia are not exporting products

However, this isn’t a catastrophe because, for one thing, Zambia has a better understanding of the spread of its SME sector. The majority are in the micro stage and are still in the early – growth phase.

“Approximately 7% of respondent firms were exporters while 43% were importers. More than half of the surveyed enterprises were also part of a value chain, producing goods and services as per their buyers’ requirements. Most of the surveyed businesses were young, with 69% in operation for fewer than 10 years. On average, 21% of employees were less than 25 years old and 32% were women.”

ITC (Promoting SME Competitiveness in Zambia Report)

However, that is, in some ways, a good thing because this at the very least means that the situational awareness the authorities have on the matter of SMEs has improved from what it was in 2008.

Formalisation of the SME Sector

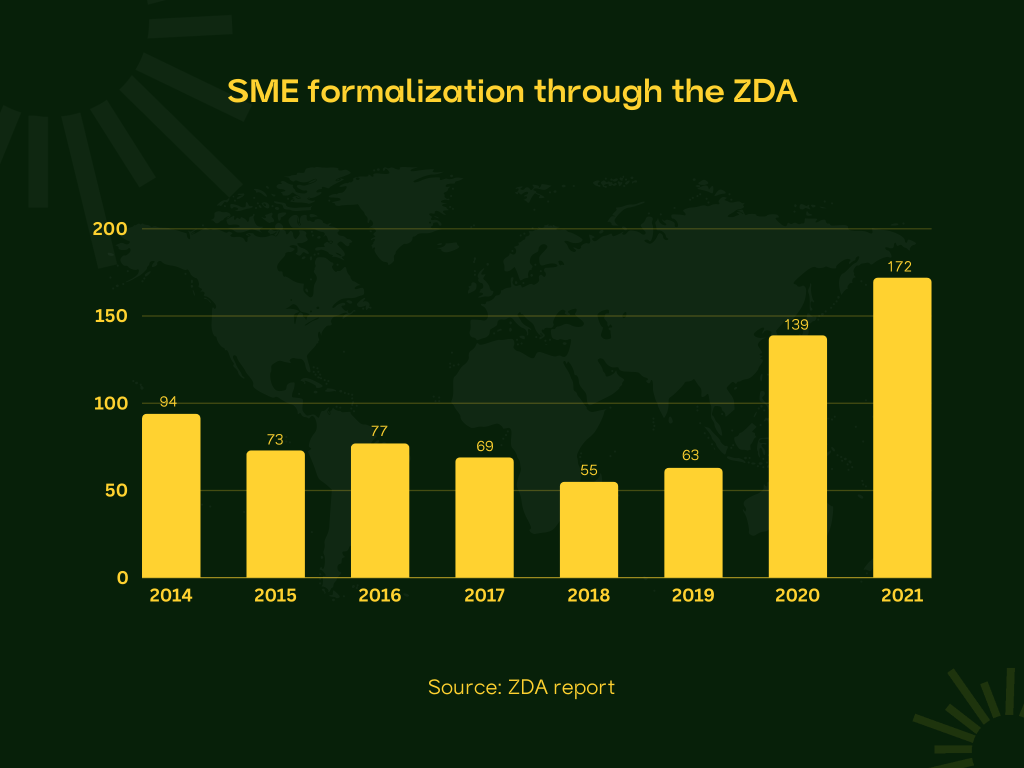

A key metric in understanding the effectiveness of the SME is looking at the number of informal companies that have made the transition to being a legal entity.

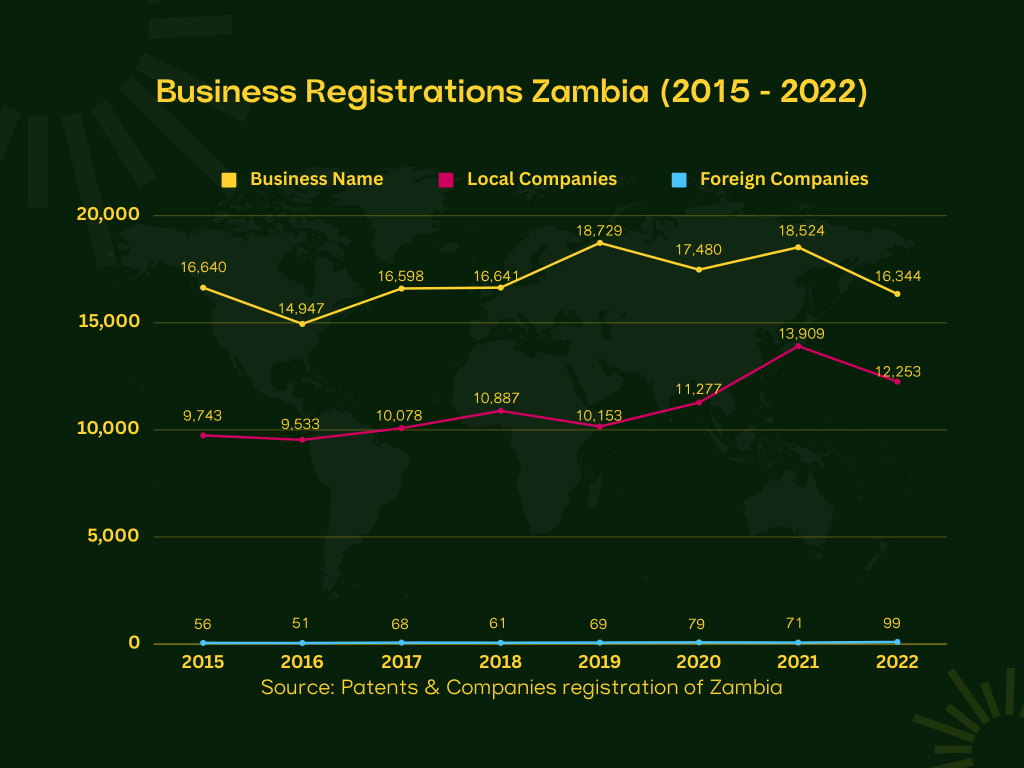

The overview of the number comes from the Patents and Companies Registration of Zambia which has shown some seriously impressive numbers of registered businesses in the country.

According to the Agency’s reports from 2015 to 2022 a total of 87,833 local companies were registered. However, the reporting is not consistent on the line of business these entities are registered for, the number from 2022 gives us an idea of what the trend has been over the years.

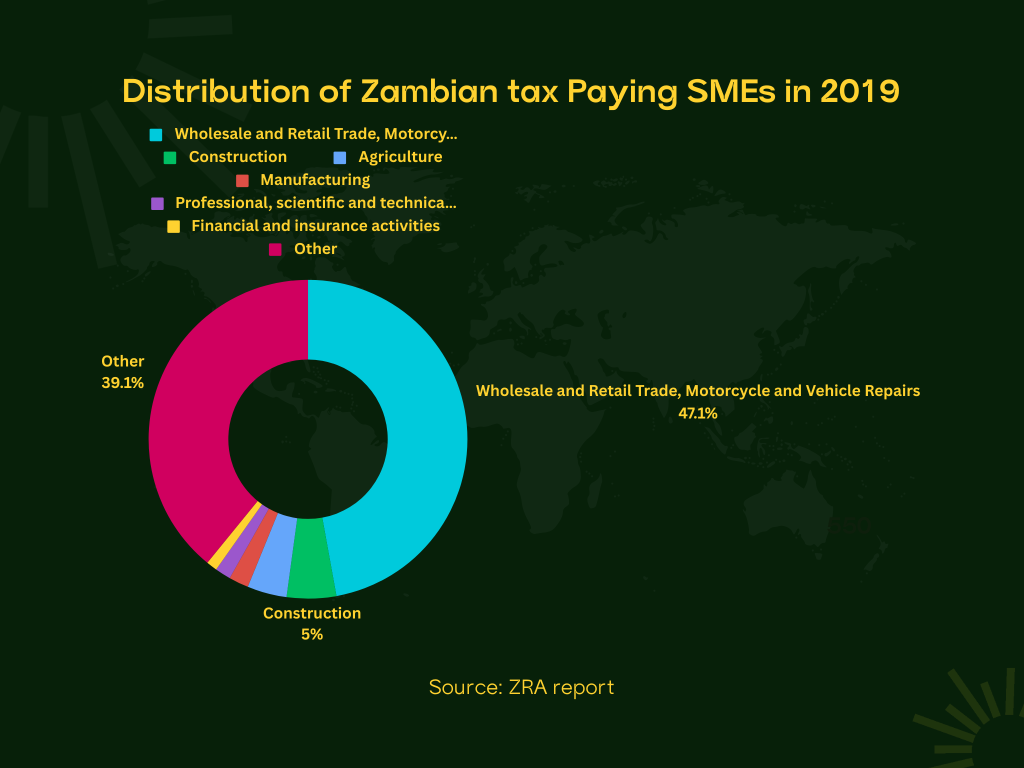

Wholesale and Retail Trade as well as Repair of Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles making up the majority of registrations is hardly surprising because that industry (if it’s fair to call it that) in SADC has been one of the most active.

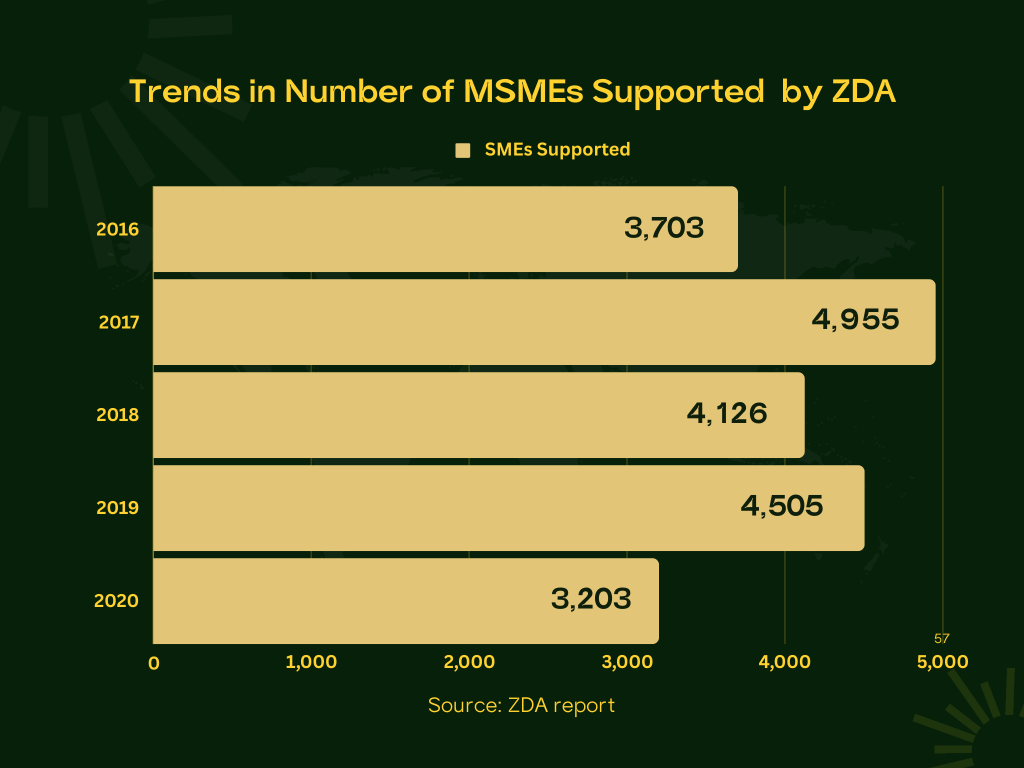

It’s important to mention that these may not all be SMEs, however, a good number of them might be. This assumption is coming from observations from the Zambian Development Agency Reports which state in 2017 that its work to assist SMEs was largely limited by its centralised operations.

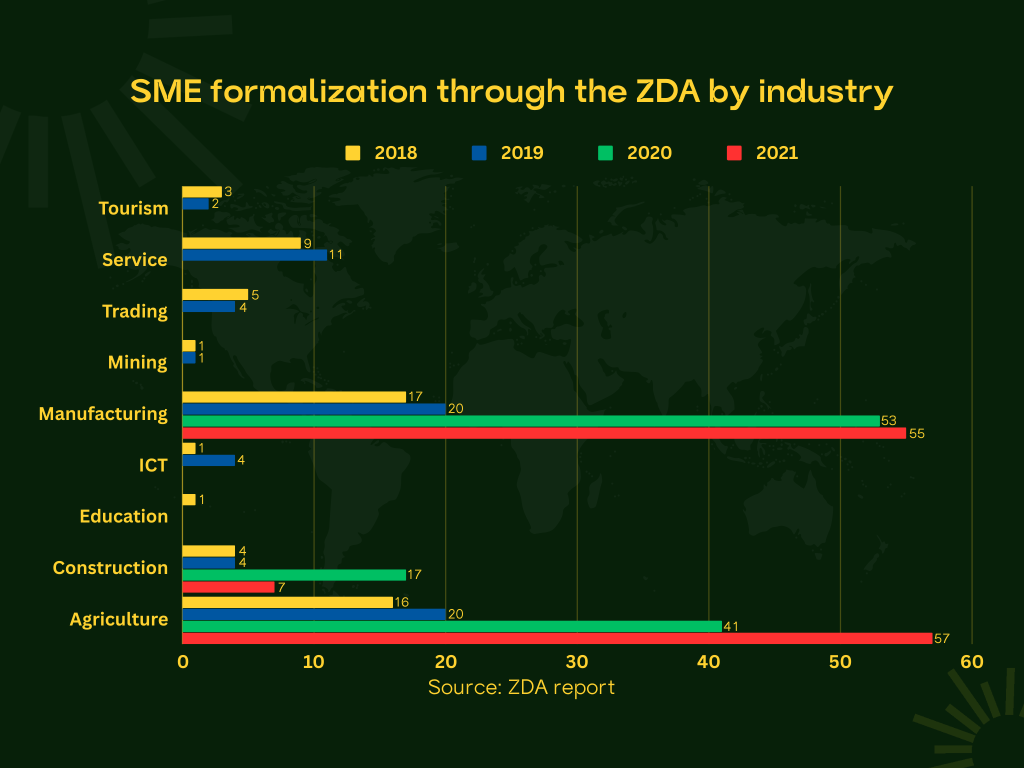

The proportion of these formalised SMEs is also an indicator of the focus of the ZDA and the economic viability of industries in Zambia.

Unlike the general company registrations, the ZDA reports, from all the entities that it has worked with heavily lean toward Manufacturing, Agriculture, and Construction which might be a policy point for the organisation if we are looking at the spread for general company registrations.

That being said, the number of SMEs registered through the ZDA does not tell the whole story. It appears there is a melding of those who formalise independently and then go on to work with the ZDA in its entrepreneurial development programmes, outreach programs, and international exhibitions participation among other initiatives.

Inclusion of SMEs in the tax system

This, in my opinion, is the most fascinating of all the metrics because the sheer amount of effort that has been put into making this possible by the Zambian Authorities should be commended.

The agency in question is the Zambia Revenue Authority (ZRA) which has taken an “Inclusion at all Costs” stance to getting the SME sector in the country to contribute to national revenue collections but this was done in, what I think, are very progressive means.

2011

Efforts to this cause started as early as 2011 when the Zambia Revenue Authority (ZRA) conducted a short-term consultancy on SME Taxation which was tasked to understand and detect the reasons for poor tax compliance among SMEs. The key finding of that study was that service delivery and information systems had to be improved. Furthermore, developing a monitoring and evaluation framework that was tailored to the needs of the ZRA and its field offices was crucial.

In 2014 the ZRA took up recommendations from the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) by way of a sponsored study on Small and Medium Taxpayers. The study identified four “priority sectors” which were:

- Wholesale and retail trade

- Construction

- Transportation

- Real-estate activities.

These areas were of particular interest because they were predominantly cash-based and therefore fell beyond the bounds of the Authority when it came to effectively tracking the transactions. A further study was undertaken in that year to understand the presumptive tax situation in Zambia to understand more effective means of revenue collection.

2014

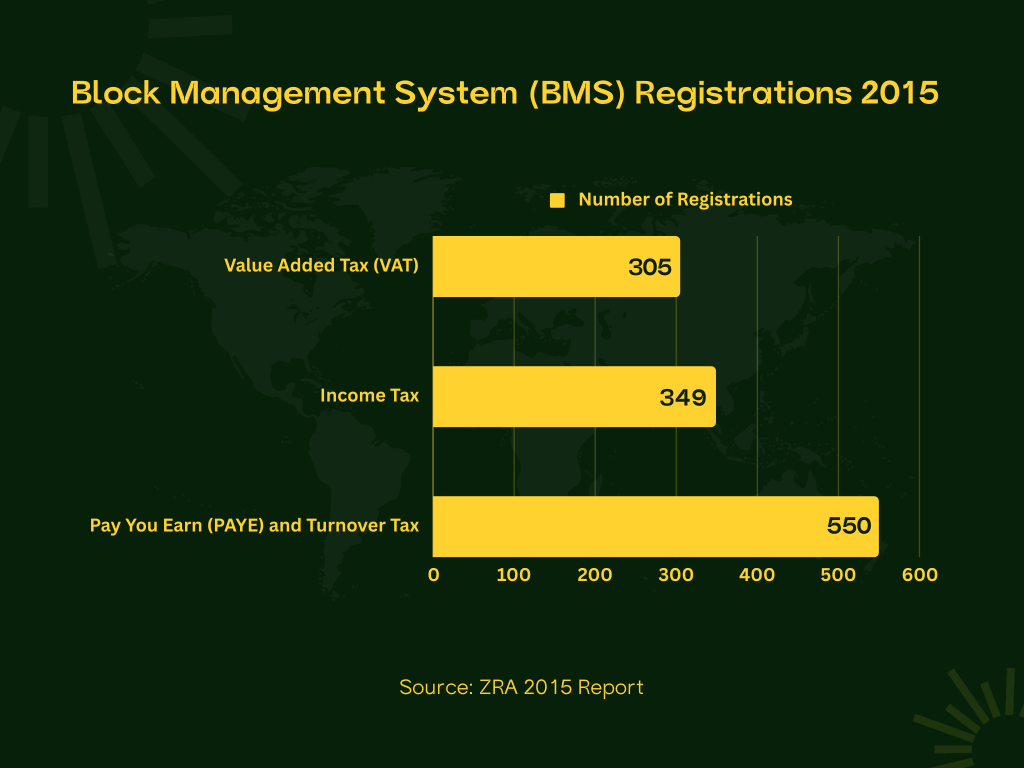

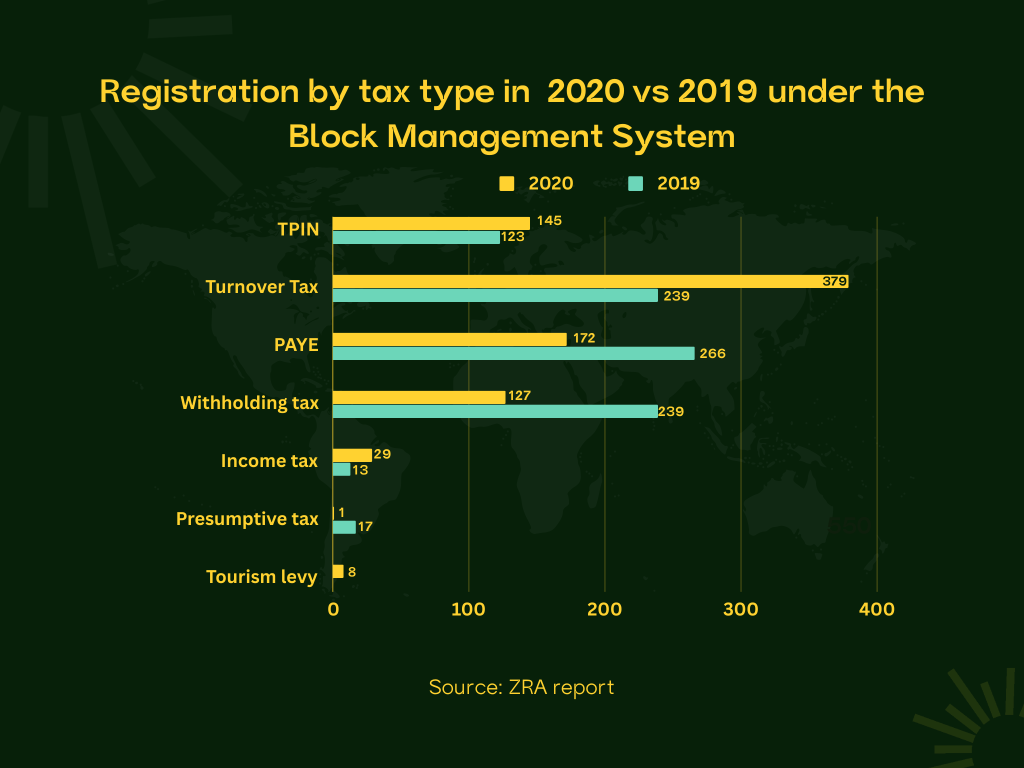

2014 also saw the continuation of the Block Management System (BMS) which is a way to monitor tax compliance and increase the taxpayer base. At the time, the BMS had 810 taxpayers on the system and a migration process was done to take 725 of those taxpayers to the new TaxOnline platform.

2015

The following year, the ZRA (with the support of GIZ) continued building up it capacity of its officer to deal with SME taxpayers. This was also supported by training done in the International Standard of Industrial Classification (ISIC) to better equip its staff with the knowledge to correctly classify economic entities through ISIC standards adopted through the TaxOnline compliance platform.

“In terms of filing compliance, the Small and Medium Taxpayer Office recorded filing compliance rates of 33 per cent for Turnover Tax; 54 per cent for VAT; 31 per cent for PAYE and 15 per cent for final income tax returns. This performance was still far below the average divisional return filing rate of 86 per cent.”

Zambia Revenue Authority 2015 Annual Report

These efforts were further aided by door-to-door education campaigns in Lusaka that sought to improve compliance with withholding tax on rental income and to promote the use of the TaxOnline e-services platform.

2016

“The Authority continues to prioritise the taxation of the Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). During the year, the focus of GIZ support to SME taxation was to improve the quality of tax audits, increase public tax awareness and improve service delivery.”

Zambian Revenue Authority (ZRA)

To aid in this the GIZ brought officers from the Bavarian Tax Authority to assist in building the capacity of the ZRA officers. The officers had meetings with the project team to develop context and an understanding of the audit support needed in good practice and techniques for real estate, financial services as well as other banking and insurance and services sectors. The conclusion made from the engagements in 2011 held, and the cash-based transaction industries of construction, wholesale and retail trade were seen as areas with a lot of potential for revenue collection.

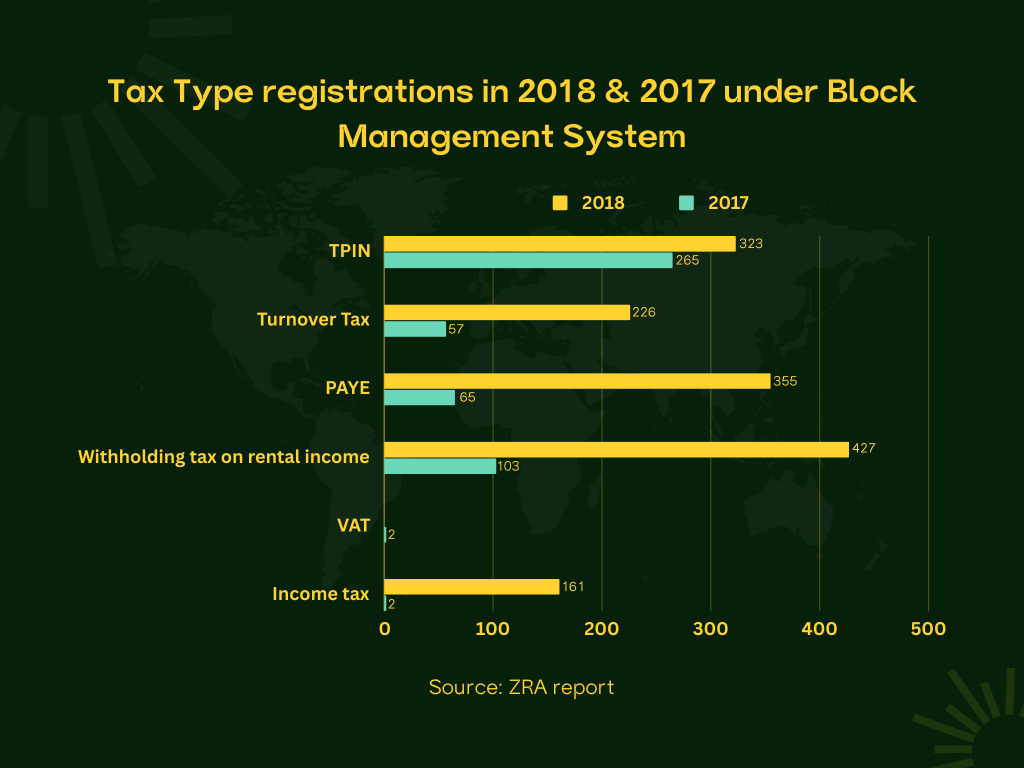

When it comes to tax filing compliance, the Small and Medium Taxpayer Office recorded filing compliance rates of 29% for Turnover Tax 64.5% for VAT 48.5% for PAYE and 18% for final income tax returns.

2018

ZRA began developing, in conjunction with the GIZ, a tax platform that was titled Zambia Mobile Electronic Taxations (ZAMet). The goal of this initiative was to allow taxpayers to file and pay taxes via mobile phones without needing an internet connection.

The authority also instituted Tax Invoice Management Systems (TIMS) that were mandatory for every taxpayer registered for Insurance Premium Levy, Tourism Levy and VAT. This would be done through the installation and use of Electronic Fiscal Devices (EFDs) which would transmit data to the ZRA. Although it was in its pilot phase in 2018, 2,194 taxpayers were trained to use the EFDs. Engagements were also held with Point-of-Sale Machine vendors and retailers to interface with TIMS.

2019

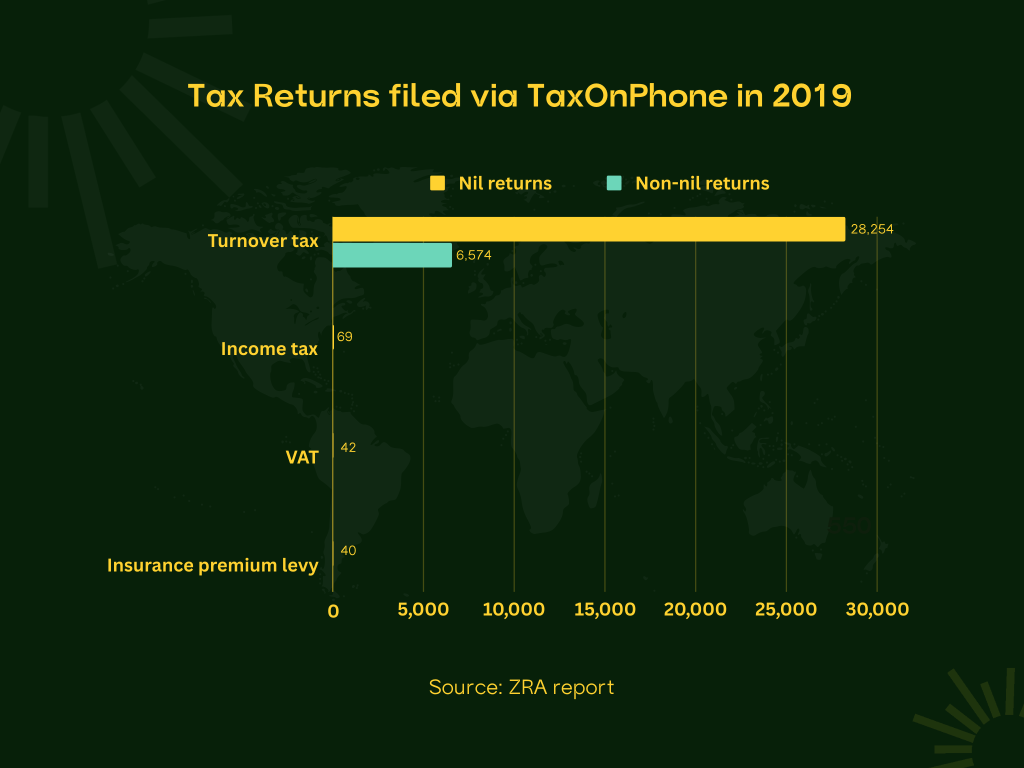

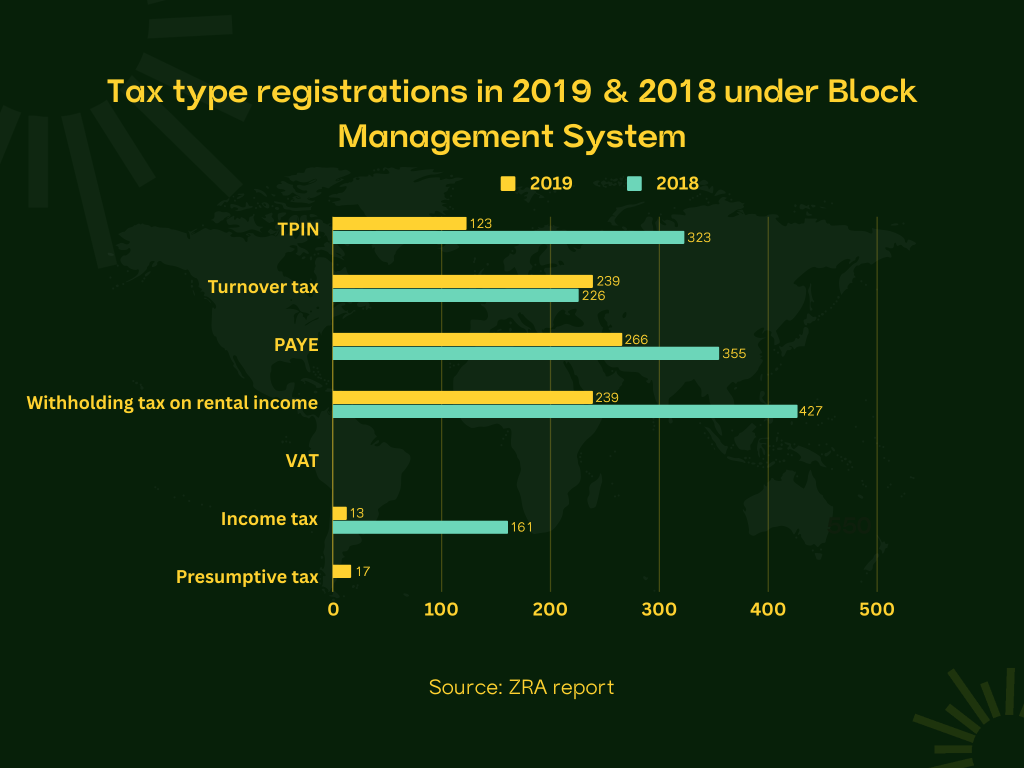

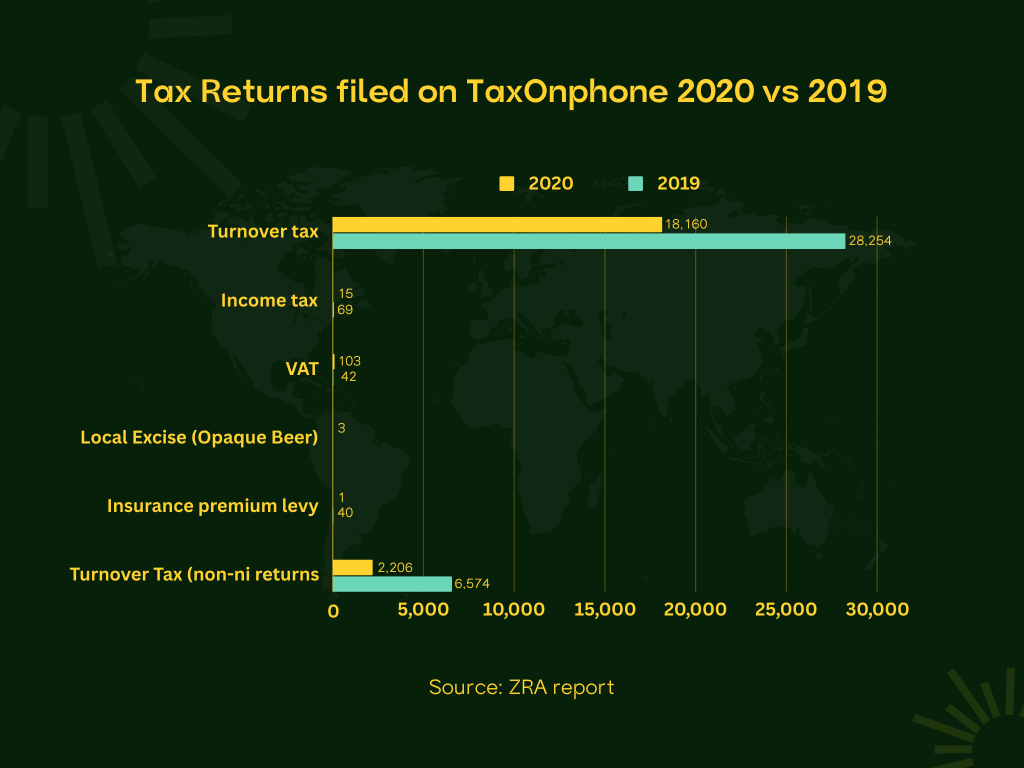

The ZRA launched the mobile internet-free platform TaxOnPhone (previously known as the Zambia Mobile Electronic Taxations). It allows taxpayers to file tax returns and review their tax compliance status on their mobile devices. At the end of 2019, the platform recorded 81,788 TPINs and seven tax-type registrations.

TaxOnPhone received 34,979 returns. Of these, 6,574 were non-nil returns with liabilities amounting to K1.7 million by the end of 2019.

The second phase of the EFD rollout was initiated with the procurement and distribution of 2,000 Fiscal Cash Registers (FCRs) and 3,000 Electronic Signature Devices (ESDs). At the end of 2019, 2,883 FCRs were distributed out of the targeted 4,000 FCRs

2020

The TaxOnPhone platform was further supported by the launch of a mobile application called TaxOnApp which was launched at the end of 2020.

“TaxOnApp enables taxpayers to access various ZRA e-services including TPIN and tax type registration or deregistration, return filing, tax payments, tax education and search for a Customs bill of entry. The internet-based application therefore augmented the Authority’s efforts to further simplify tax compliance procedures, reduce taxpayers’ compliance costs and improve efficiency in the processing of taxpayer information.”

ZRA

2021

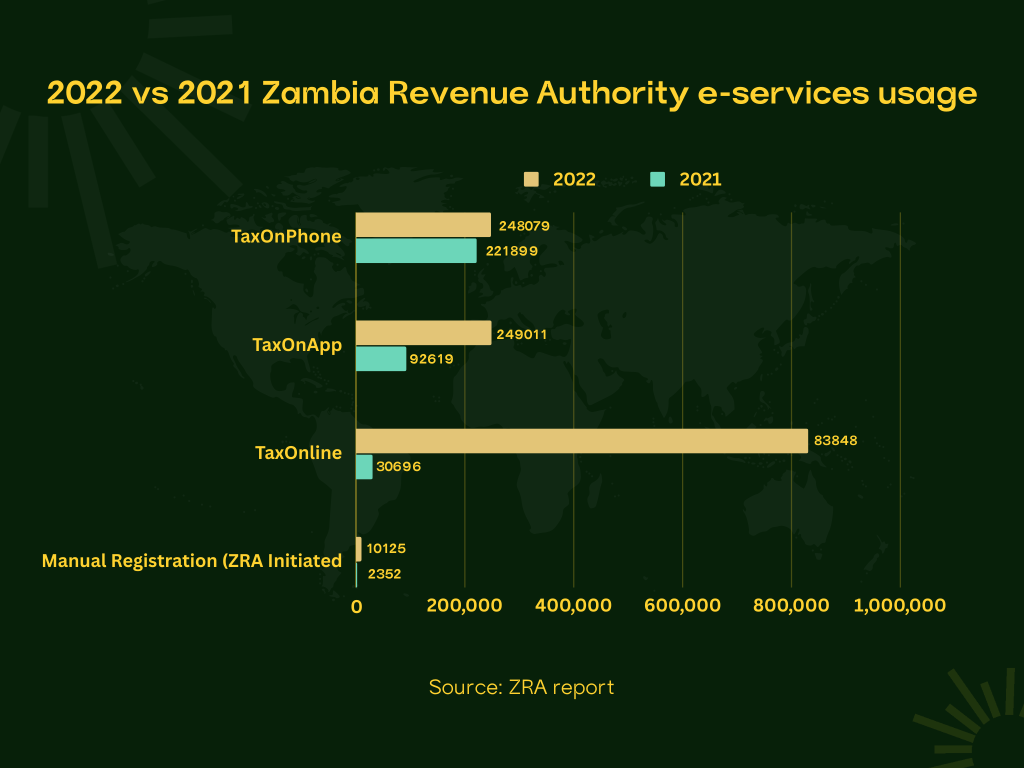

This year was marked by a massive 221,889 registrations done via TaxOnPhone which was considerably more than the 154,458 registrations in 2020. This also coincided with the tax filing situation registering a greater improvement from the 2020 figures.

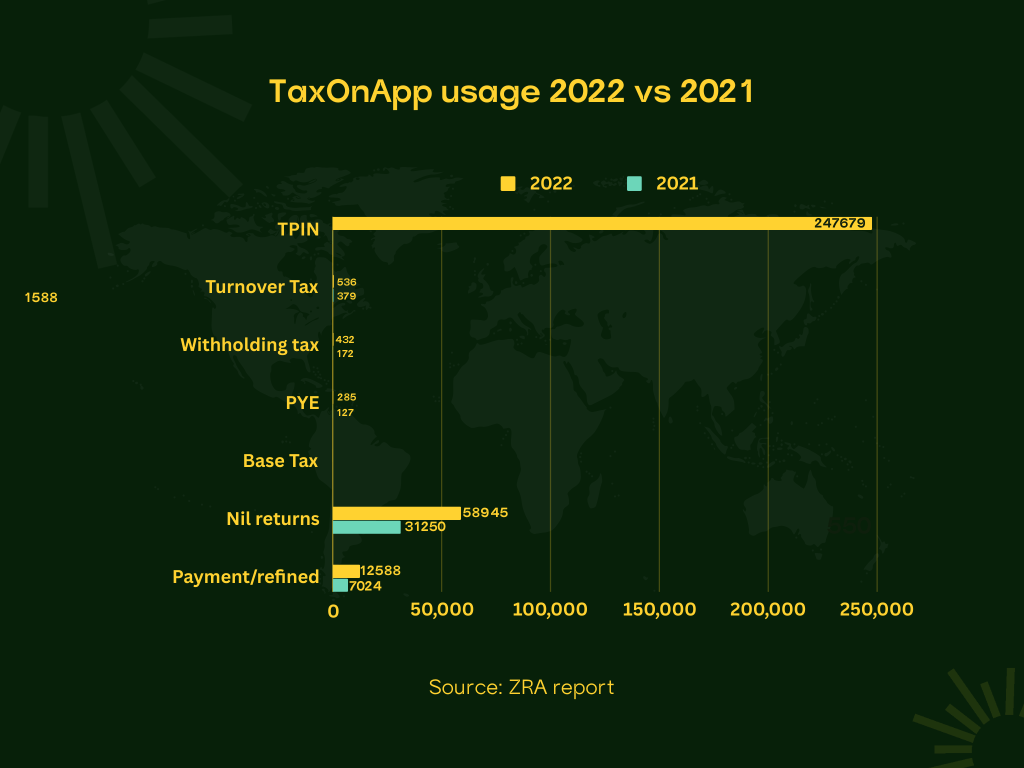

TaxOnApp also saw a good number of registrations numbering 92,619 in 2021. The ZRA admitted that the high uptake was driven by TPIN registrations with turnover tax and tax registration numbering 319 and 311 respectively.

2022

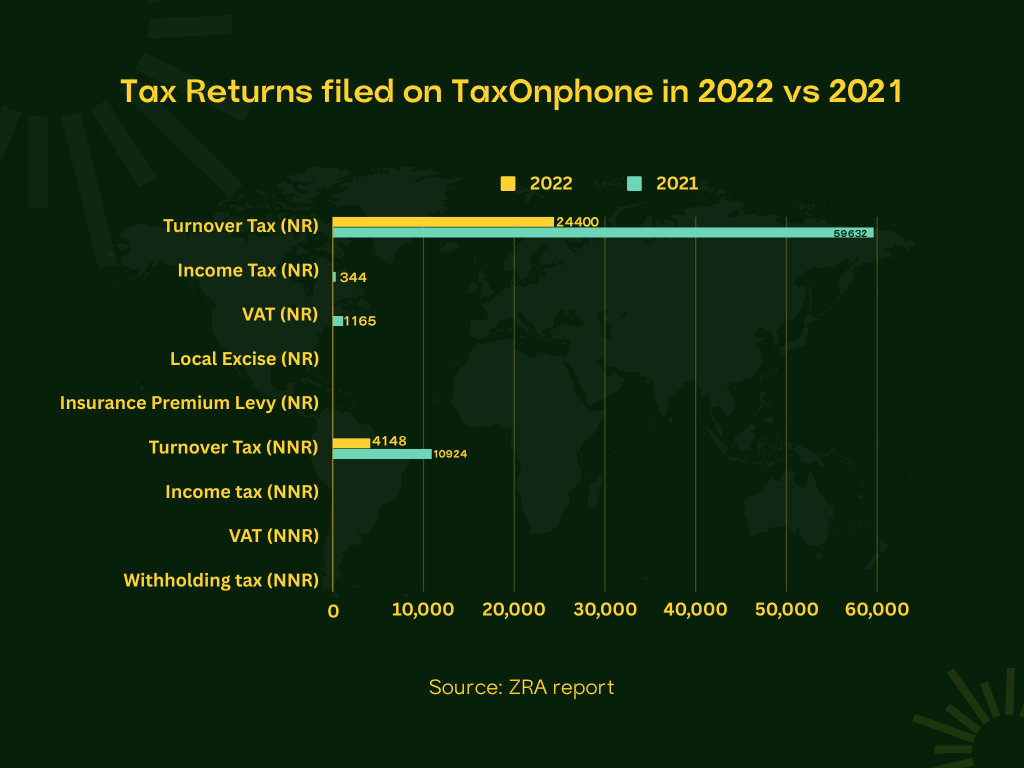

The efforts to get taxpayers to comply with regulations paid dividends in 2022 with the ZRA recording 248,079 TaxOnPhone USSD registrations which was an improvement from the 221,899 registrations recorded in the previous year.

On the other hand, 2022 marked a significant decrease in tax filings via TaxOnPhone, according to the ZRA filings fell from 72,087 in 2021 to 28,684 in 2022. This, according to the Authority, was due to its users not preferring to use the USSD platform.

That assumption was backed up by the 168.9% increase in registration on the TaxOnApp platform in 2022.

Piecemeal progress but advancing nonetheless

The tax picture fascinates me because it shows that the policy points and strategic plans by the Zambian Authorities are tackling the multifarious factors that are affecting the measurable economic influence of SMEs.

To have nearly a quarter of a million registrations from SMEs in 2022 is a number that most countries wouldn’t even dream of considering.

The adaptation of compliance to USSD to ensure inclusion was, I think, one of the key drivers of all of the ZRA’s progress. According to the GIZ, Zambia collects US$20,000 in taxes per month through TaxOnPhone. The preference to migrate from the USSD-based platform to the application shows the development of the program to the point there is a greater pool of people who can afford broader internet services to access the mobile application.

Additionally, there has been a great appreciation in the revenue collection by the Zambia Revenue Authority over the years.

Whether this could be credited to SME policy and interventions made by the Zambian Government and its agencies is not clear. Zambia has, through its relative stability and strategic location in North-South Trade, been able to attract foreign investment and economic growth. However, it can be seen as progress in the effort to formalise the informal SME sector and make greater contributions to the economy.

Zambia is setting a good example in tackling the SME informal sector

As earlier mentioned, shortcuts don’t achieve much unless one can pull them off. Zambia represents a very deliberate effort to build a solid foundation for the inclusion of the SME sector. The progress referenced here does go far enough because of the availability of more direct data that would reduce the need for speculation and extrapolations.

In saying that Zambia has recently released an updated SME Policy. At the end of 2023, they revised the 2008 document and it stated some of the achievements that they were able to make in the decade and a half the old policy has been in effect.

In the new document, the country had 110,508 registered tax-paying SMEs. This number represented a 27% growth in formal enterprises from estimates in 2012. The spread of those industries is as follows:

As an example to the SADC region (aside from South Africa), Zambia is a shining example of what can be possible and it’ll be interesting to see what they can achieve with the 2023 MSME Policy.