The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe recently encouraged financial institutions in the country to prioritise low-cost bank accounts in a move to incentivise use of digital payment channels over cash:

Financial institutions are encouraged to scale up financial inclusion through opening of more no-frills (low-cost) accounts. This measure will promote usage of banking services and financial products, including increased use of bank cards, digital financial services and other cash-lite means of payments in the economy.

In order to complement efforts to formalise the economy and to give more impetus to the use of non-cash-based means of payment in the economy, it is recommended that Government considers removing Intermediated Money Transfer Tax (IMTT) on transactions that are intermediated through plastic bank cards and other digital platforms.

Monetary Policy Committee resolutions

Low-cost bank accounts are the accounts that have limited “Know Your Customer” (KYC) requirements with a view to banking individuals in lower income segments. It’s interesting that the Reserve Bank is taking the position to encourage these accounts given the history. Between 2016 and 2020 low-cost bank accounts were growing at an impressive rate before interventions by the central bank took the sails out of the wind of the banking sector.

There are a few reasons for the decline of bank accounts in the country post-2020. First is that the Central bank went on a witch-hunt which primarily targeted mobile money service providers. The central bank’s reasoning was that because of the lax KYC requirements mobile money services had, illegal money changers were using mobile money to drive foreign currency rates up and basically disrupt the economy. Mobile money was temporarily banned. When it went back online, restrictive weekly and monthly transaction limits were set in place for both mobile money and consumer bank accounts.

The effect of such a witch-hunt was as follows. Using bank accounts became more complicated since you had to keep track of how close to your weekly/monthly limits you were. Secondly whilst the primary targets were mobile money accounts – banks were naturally also hesitant to keep propping up their low-KYC accounts. The thought process here is simple – what if the “rogue elements” who have been using mobile money to disrupt the economy turn to low-KYC bank accounts. Naturally the growth stops and at the centre of all this was central bank directives.

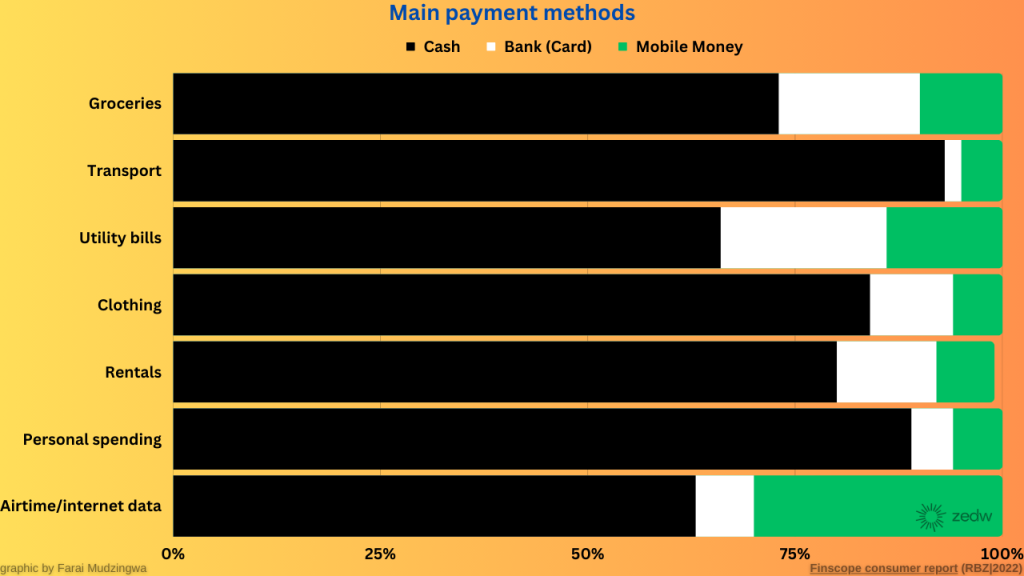

If the second order consequence of the 2020 witch hunt was to scare institutions offering low-cost accounts, the third order consequence was that these limits frustrated regular citizens and pushed them back to cash. As the friction of using bank accounts or mobile money increasing people started turning to cash again. Of course there’s more nuance to this. The local currency was on a downward spiral and everyone from consumers to business wanted to get their hands on the sweet (and global) US dollar. What RBZ effectively did though was increase incentive to not use local currency by limiting the functionality of mobile money and bank accounts resulting in the usage pattern we see in the image above (i.e an economy that prefers cash).

Whilst that was a long prologue – I feel that this is necessary context and why I’m personally surprised to learn that the central bank is now pushing for adoption of low-cost bank accounts now. The precedent the central bank has set is that of a master who is all stick and no carrot – who is to say bank accounts will actually take this seriously given that the regulator could wake up in a sour mood and change tune on them.

There are two ways – (maybe three actually) – to process this information.

- To the cynical – this is lip service for the central bank to posture that financial inclusion is still a core concern and they are actively pushing for it.

- To the optimists – this is a genuine push. By having people use bank accounts again the downward spiral of the ZW$ can be slowed down and the currency can maintain some strength. The removal of the IMTT tax is also a great incentive as it’s one less charge bringing using digital channels closer to cash – though it’s important to note that the central bank doesn’t seem to have the final call on that.

- (These men and women are throwing anything at the wall and seeing what sticks.) GOD SAVE US ALL if it’s the third.

Potential benefits

If we put my jokes and general cynicism aside, what could be some of the benefits of this strategy?

Well the first and clearest is the aforementioned fact that if the 2% tax is removed when transacting using digital as called for by the central banks it will become cheaper to transact. Whilst cost is not the be-all and end-all it is a huge factor in an economy where 64.5% of inhabitants earn less than $3.65/day – below the World Bank international poverty line. Those charges make a difference. The 2% tax is also maligned beyond consumers with businesses mentioning how it has become a thorn in their operations.

A striking difference in Zimbabwe’s tax revenue breakdown when compared to other countries is the contribution of the Intermediary Transfer Tax, or IMTT. This 2% charge is applied on all transactions and, while this was initially meant to capture tax revenue from the informal sector, has been a pain in the neck for the formal sector as they remain the only players who largely transact using formal channels. Several players have lamented the burdensome tax’s effect on the sustainability of their businesses. While the IMTT has raked in considerable tax revenue for the local government, economic theory on tax suggests the tax could push more business players to informalize.

Tafara Mtutu – Head of research at Morgan & Co

An important caveat to keep in mind is that Zimbabwe effectively has 3 tiers of pricing:

- Digital ZW$ – the least attractive price to consumers since they have to contend with taxes, bank charges and the fact that shops tend to price significantly above the exchange rate to ensure they don’t make a loss whilst the currency is weakening.

- Cash ZW$ – this is a bit more competitive since there aren’t bank charges and cash is more desirable. Informal businesses at times even have preferential prices for ZW$ cash transactions.

- US$ cash – this is the most desired medium of exchange and business tend to price goods/services most attractively for buyers using this medium.

Removal of the 2% tax for digital transactions could mean that prices of goods and services in ZW$ come closer to US$ cash prices.

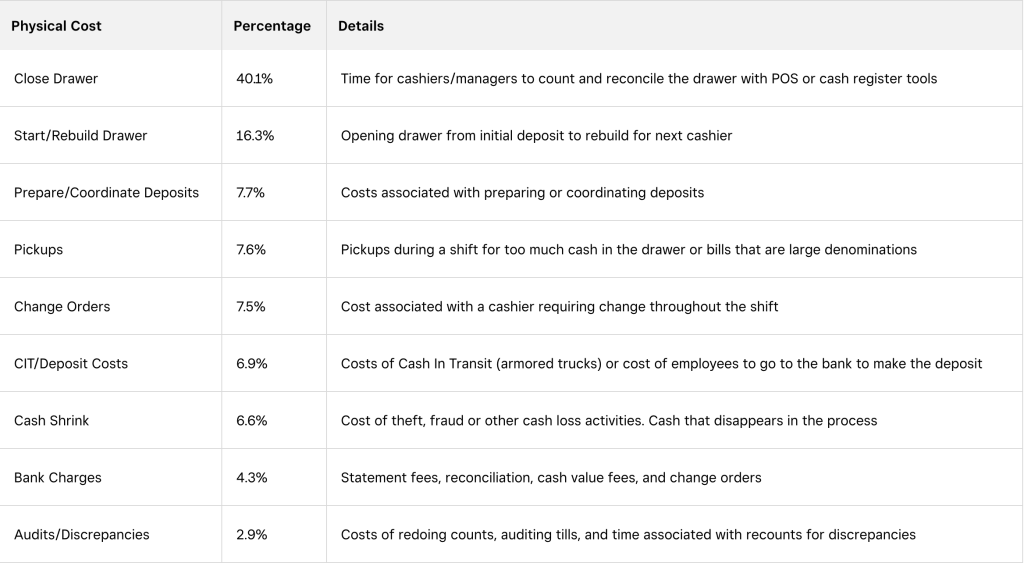

Another benefit of low-cost accounts which I hinted at already is that they can reduce the reliance on cash in the economy, which can have several advantages. Cash transactions are costly, risky, and inefficient. They incur high handling and transportation costs for both banks and customers. They expose people to theft, fraud, and corruption. They also limit the availability of data and information that can be used for policy making, monitoring, and evaluation. Cash also has a time cost as books have to be reconciled and the cash manually counted. By encouraging people to use banking products instead of cash, low-cost accounts can help lower transaction costs, improve security, and increase transparency.

Source: SquareUp

The Finscope consumer report published by the central bank (2022) conducted by the central bank indicated that 38% of respondents felt they had lost money because of currency conversion. This is a pain point which could be solved by the promotion of local currency usage along with use adoption of digital channels. If less people are having to convert their ZW$ to US$ they don’t have to worry about being ripped of by money changers who can sometimes offer what seems like random exchange rates to regular people.

Challenges

The biggest challenge is that a big determinant factor for all this is whether or not the Ministry of Finance would actually remove the 2% tax. With the country moving to cash again the share of revenue generated by IMTT tax for Zimbabwe’s Revenue Authority has fallen to 6.83% but prioritising digital channels would potentially see that number rise. In Q2 of 2022 it accounted for 9.24% for the tax collectors. Will that institution and by extension – the government be happy to sacrifice that slice of pie?

In December of 2022, Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube was adamant that the tax would remain after local government’s had requested to be exempt from paying the tax. Businesses, domestic remittance players and other branches of government have been lobbying for its removal but the finance ministry usually brushes away those requests.