There’s a metric I often turn to when contextualizing why it’s so hard for businesses to operate in Zimbabwe (and sometimes broader Africa). Poverty levels are significantly high with 64.5% of the population earning less than $3.65/day which results in an economy where majority of consumers cannot afford to pay outright for essential items such as mobile phones, home furniture and appliances and vehicles. This inability to spend is compounded by the fact that there are very few credit options available to ordinary Zimbabweans which means if you fancy something you’re more often than not having to pay for it all at once…

At its core, credit facilitates increased consumption and investment. It benefits different sectors of the economy in different ways. For businesses, credit allows them to finance their operations, expanding production, invest in new technologies, and innovate. For consumers, credit allows them to purchase goods and services that they need or want, such as housing, education, health care, and leisure. For governments, credit allows them to fund public spending, such as infrastructure, social services, and defense. A well-functioning credit system expands the productive capacity of an economy, boosting overall output and generating wealth – precisely what is missing in most developing countries on the continent.

“With better access to consumer credit facilities, people in the low and middle-income class will have a better opportunity to afford items that improve their lifestyles and livelihoods. For example, the woman who sells cold drinks by the roadside, packed in a cooler along with blocks of ice and makes less than $100 in monthly profits is unlikely to afford outright payment for a freezer. However, with access to consumer credit facilities, she can buy a freezer which will serve and grow her micro-business and, more often than not, also eases household cooking chores.”

Fehintolu Olaogun CEO and Co-founder, CredPal | World Economic Forum

Credit also has some challenges and risks associated with it. Ensuring that it is available and affordable for those who need it, especially for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and low-income households is one such issue and the one we will be mainly focusing on today… Other challenges include regulation of the credit market to prevent fraud, abuse, and predatory lending practices. One of the main risks is that credit can create excessive debt and leverage, which can lead to financial instability and crises. Another risk is that credit can fuel inflation and asset bubbles, which can distort prices and allocation of resources.

Mobile money – a pendulum shift?

Mobile money has been heralded as a revolutionary financial technology instrument because of the impact it has had on the continent. In the case of EcoCash which was launched in 2011 and has grown to nearly 8 million subscribers – this impact can’t be downplayed.

Around the time of EcoCash’s entry into the market – only 24% of Zimbabweans had access to financial services (about 2.8 million people at the time). By mid 2023, EcoCash alone has 7.75 million registered subscribers on their mobile money platform.

Beyond just getting people to use mobile money for transacting or sending money, the use cases have been varied, spilling over into established insurance products and experiments with savings offerings. EcoCash’s annual results indicated that they are currently reaching 3 million customers through their different insurance products served under the EcoSure brand.

The true indication of the ubiquity of EcoCash however is truly represented when you look at the national transaction switch where the mobile money service was used to conduct 80% of the transactions. Their percentage of transaction values is significantly lower at 6% but that is because of the nature of transactions and dwindling utility which we will touch on later…

As for credit offerings – the point of discussion here, EcoCash has also been present and growing its footprint. The financial service provider has given out 7x more loans in 2023 (902,875) than it did in 2021 (132,413). Given this ubiquity of the mobile money service in our lives, Dotzedw wanted to explore the possibility that the mobile money provider could have been a starting point in regard to a national credit scoring service.

Credit demand & supply in Zimbabwe

We spoke of the under-developed financial system that existed a decade ago. One of the byproducts of such a financial system is that many institutions simply don’t have enough information to actually be able to predict whether a loan will be repaid or not. This is why for years Zimbabwean banks have been mulling over the idea of establishing a co-owned credit bureau.

A research paper titled Zimbabwe:The case for a credit bureau notes that these efforts go as far back as 2009 with the credit bureau being established “to promote the exchange of credit information among lenders in the financial sector”.

“If lenders have better quality information about borrowers, this would give them (borrowers) improved access to credit which translates to greater availability of credit at lower cost. The bottom-line is that the availability of information will stimulate economic activity and growth of the economy and will reward responsible lending and borrowing.”

Zimbabwe: The case for a credit bureau | Ezekiel M Bopoto (ICT and Banking Consultant)

One of the discoveries made by researchers is that borrowers were using unaudited financial statements, hiding their history and thus making it difficult for lenders to predict whether borrowers will be able to return funds. These unaudited statements were historically prone to manipulation, masking potential risk to lenders.

The lack of a functional credit scoring system had clear results – the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio rose as high as 15% (when the acceptable rate is 5%) by 2015. Lenders were only looking at the borrower’s incomes which led to defaulting on the loans. More recently, the situation isn’t that much better with lenders over-correcting and becoming hesitant to lend which has seen the non-performing loan ratio drop to 1.58% at the end of 2022. It’s also fair to note that Zimbabwe’s policy issues have played a major role in discouraging lending.

In 2016, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe introduced bond notes – effectively meaning the country had a local currency again (in addition to the US$ and Rands that had been in use since 2009). At the end of 2017 and 2018, the non-performing loan ratio’s lay at 7% and 6.92% respectively. Both of these were closer to the ideal 5% mark we previously noted but by the end of 2019 the NPL ratio had dropped to 1.75% and a year later would fall further to 0.31% – an indicator that borrowers were paying off their loans but one that leaves out the sinister context behind which they were doing so.

This seismic shift was caused in part by legislation as Zimbabwe’s supreme court made a ruling in 2019 that under the new multi-currency system borrowers could settle their existing (US$) debts in local currency. The Zimbabwean Coalition On Debt and Development (ZIMCODD) said the ruling “disadvantages creditors considering that the two currencies in question do not carry the same purchasing power”. The problem with the ruling was that the Government insisted that the bond notes were of equal value to the US$ but the reality that played out on the ground was quite different with the US$ being in far more demand than the local tender. This meant borrowers effectively got massive portions of their loans written off.

Simply put, ZWL$1000 is currently equivalent to USD58 at the official exchange rate as of 23 January 2019. Therefore, assigning equal weight to the two currencies for debt repayment does not only kill the financial services sector but also takes away investor confidence across sectors. The domestic creditors will not be able to recover the principal amount lent, let alone the interest. Therefore, the chances for economic revival in the near future remain slim…

ZIMCODD

All this is to say, Zimbabwe’s credit landscape is fairly complicated and whilst the existence of a credit scoring system would give lenders more confidence in identifying good or bad borrowers, it still doesn’t address the policy side of the coin which has seemingly been riddled with inconsistencies that chip away at the confidence of lenders. Policy-related incidents will rear their head again later in our conversation…

Additionally, the data that exists has also been called into question when it comes to effectiveness. Income is one of the key data points lenders utilise but given that of Zimbabwe’s employed population – 28% were working in formal jobs at the end of 2022 that becomes complicated. Credit applicant’s salary level may not correctly reflect their ability to repay loans since many have income streams that are not formally recorded. This is also part of the reasons why most consumer lending offerings are now targeted at civil servants – as that is one of the few formal channels where lenders can get their money back directly from the Salary Service Bureau (SSB) whenever the civil servant gets paid thus reducing risk of default. This has historically meant that civil servants have much broader access to credit offerings than most other consumers:

Could EcoCash have built a credit scoring service?

Before the infamous mobile money ban in Zimbabwe in 2020 – there’s reason to believe that EcoCash could have been a good starting point for such a credit scoring service. The mobile money service provider has over a decade of data from millions of Zimbabweans comprising different ages and income groups. Customer segmentation could be achieved quite effectively given that Econet and Ecocash had numerous data points to profile potential borrowers stemming from their different products and services.

| Transaction type/service | Transacting capacity | Utility data | Location data | Asset data | Credit data |

| Send/Receive money | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Airtime purchase | ✓ | ||||

| Utility Bills | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Tollgates | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Motor vehicle insurance/licensing | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Health/Life insurance | ✓ | ||||

| ConnectedCar | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| ConnectedHome | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kashagi Microloan facility | ✓ | ||||

| *EcoCash Save | ✓ | ||||

| *EcoCash Payroll | ✓ |

This is enough data to inform a credit scoring algorithm and is what is currently being used to inform how much one receives via EcoCash & Steward Bank Kashagi Loans. EcoCash’s FAQ page on the loan outlines that loan limits are currently “determined by each customer’s transaction capacity. Different customers have different limits.”

There’s evidence suggesting that EcoCash could handle all this. In fact, in the mid-2010s EcoCash offered a credit service that pretty much monitored fewer transactions but still gave access to as much as US$500 in micro-credit. In 2015, the EcoCash Loans facility ranging from US$15-US$500 had fewer data points than what we’ve suggested in the table above. The vetting requirements were EcoCash and EcoCash Save usage along with airtime purchase history.

Outside of the Zimbabwean context, we’ve also seen more complex approaches adopted by Indian startup Yabx – who use machine learning to analyze mobile money transactions and telecoms data along with credit scoring bureaus & utility bills. They claim to have scored over 100 million borrowers – half of which are African.

Malawi has low access to formal financial services and Yabx decided to create a model reliant on analysis of data from the telecoms networks. Over 100,000 loans were provided with customers applying via USSD and the loans linked to their mobile money wallets.

Yabx generally tends to use a combination of data which includes any of the following;

- payment transactions;

- digital footprint data;

- utility data;

- telecoms data (which extends to location, airtime & data purchases etc);

- credit bureau data

Source: GSMA

This combination of data allows them to issue out loans of between $5-$10,000 to everything from individuals to retailers. EcoCash as illustrated by the table above has access similar data points and this is before we consider their access to insurance data as well – suggesting they have data sets that can do a decent job of profiling customers.

It’s important to also acknowledge that EcoCash did make some significant efforts that would have actually bolstered their position in regard to credit scoring. The mobile money service rolled out Payroll for the purposes of processing salaries and bulk payments and in 2018 this was connected to the SSB which was yet another potential datapoint.

I have reservations regarding whether banks would actually have been open to sharing their data with EcoCash considering the occasionally acrimonious relationship the mobile money institution has had with traditional banking institutions…

So what’s the hold up now?

The astute among you will have noticed that the heading for the previous section was in the past tense suggesting that there was a window of opportunity for such a mobile-money-led scoring agency. Aforementioned policy interference means that the effectiveness of such a solution is now handicapped. In 2020, the RBZ banned mobile money altogether – accusing the service and providers of driving up exchange rates and destabilizing the economy.

The central bank’s reasoning was that because of the lax KYC requirements mobile money services had, illegal money changers were using mobile money to drive foreign currency rates up and basically sabotaging the economy. Mobile money was temporarily banned. When it went back online, restrictive weekly and monthly transaction limits were set in place for both mobile money and consumer bank accounts. These limits are what would potentially make it hard to separate users as there’s a hard cap on transactions that limits user differentiation. A side-effect of that ban has been that using banking/mobile money services has added friction to the mobile money user experience since consumers constantly have to be thinking about these.

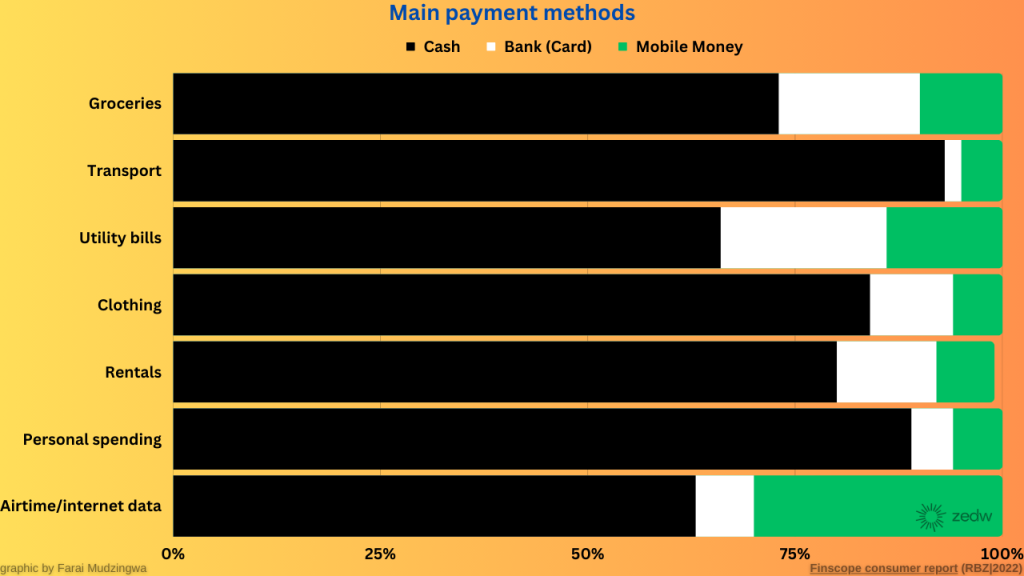

A second order consequence of these limits was frustrating consumers and pushed them back to cash. (Though this was also in combination with the US$ being a more attractive currency that merchants want to acquire and thus price favourably for). As of 2022, Zimbabweans were predominantly using cash to pay for goods and services which presents another problem.

The growing or continued usage of cash across the economy makes it difficult for any credit scoring system to profile potential borrowers as a number of transactions simply can’t be traced to any particular individual therefore bringing us back to the problem of incomplete data.

Where to from here?

In 2017, the Reserve Bank announced that they were in the process of implementing a credit registry system. The system provides credit reports to subscribers with the following information:

- Credit Registry Report – the report lists all available information about the subject in the database. It includes personal information from data providers and available information from public sources.

- Credit Registry Report Plus – In addition to the information provided in the Credit Registry Report, the Credit Registry Report Plus contains scoring information.

- Scoring Report (Credit Registry Predictor) – a report with detailed scoring information of subject including calculation of the historical scoring.

- Consumer Report – a report intended for the consumer to inform them about their information stored in the Credit Registry. In addition, it contains information about data providers and report inquiries made on the consumer.

- Consumer Report Plus – In addition to the information provided in the Consumer Report, the Consumer Report Plus contains scoring information about the consume

This registry is made up of all banks and shortly after its launch in 2017 – the Office of the President and Cabinet (OPC) announced that 84% of loans had been uploaded to the registry – a number which grew to 97% by the midway point of that year. Reserve Bank data shows that usage of the system has been growing with enquiries growing from 275,829 in 2020 to 2,570,658 by the end of 2022. Earlier this year, the RBZ also announced that they were onboarding Microfinance Institutions as data providers on the Credit Registry system.

The central bank’s efforts in regards to improving credit access aren’t only limited to the Credit Registry system either. On November 4, 2022 the Movable Property Security Interests Act came into effect which effectively greenlit the operations of the Collateral Registry – a database of ownership of movable assets allowing borrowers to prove their creditworthiness. The Collateral Registry came into effect on the 18th of November and as of the midway point of the year, 46 institutions comprising of law firms, banks and MFIs had entered the database.

Ultimately, it seems things are moving along respectably when it comes to building out a unified credit scoring system in Zimbabwe…

The one caveat with the model being adopted by the RBZ is that it doesn’t seem to take into account mobile money either as service providers or users of the data which could be a missed opportunity as mobile money is the biggest driver of financial inclusion in the country. This might result in the expansion of a credit market the excludes access to those without bank accounts. Beyond financial exclusion if mobile money service providers aren’t incorporated valuable data that could be used to flesh out the credit registry is being missed.

What could be the impact?

Ideally as the RBZ’s Credit Registry grows the desired outcomes will be that this ultimately incentivizes the electronic transactions. If access to consumer credit is tied to having a good score and presence within the Credit Registry and then Zimbabweans might finally have a real incentive to move away from cash. The point of attraction here will of course be the ability for regular people to consume more through credit mechanisms than they otherwise would have using existing transaction methods.

Increasing electronic transactions has been one of the RBZ key goals for a while now it will solve a number of problems, mainly encouraging the use of local currency over the US$ whilst also reducing the risks of fraud because of the traceability of electronic transactions.

A byproduct of this will be more credit usage as the data from electronic transactions will be further incorporated into credit scoring models, allowing lenders to gain a comprehensive and accurate picture of borrowers’ financial behaviour allowing further lending and increasing the existence of enticing buy now pay later (BNPL) offerings in the credit landscape.

As we indicated earlier a functional credit system will increase spending and spending options by reducing barriers to entry for consumers. BNPL providers can expand their reach to previously underserved demographics, such as young adults, gig workers, and those with limited credit history.

All these are hypothetical gains of course and these things tend to look good on paper. Once you factor in currency volatility and policy inconsistency, my feeling is ultimately that things won’t evolve as simply as I make it out above but it is still good to see that active efforts, which were long overdue, are finally being made to address Zimbabwe’s credit market (or lack thereof)…