Over the last 18 months – Artificial Intelligence (AI) has started to gain momentum that is making it next to impossible for most of us to ignore it… Most people working in a skilled capacity are currently forced to contend with the question – what will work look like 5 to 10 years from now? Beyond what work will look like the next question to contend with is whether or not the country you’re in is priming itself to be prepared for this technological revolution.

We studied annual AI readiness reports from Oxford Insights from 2019-2023. The reports are an annual assessment of the readiness of countries to adopt AI in public services and business, spanning over 190 countries making it one of the most comprehensive sources of information on AI.

The AI Readiness Index explores a country’s performance across the following pillars and then assigns a score which determines the country’s ranking:

| Governance | Ranks the government’s strategic vision for how it develops and governs AI, supported byappropriate regulation and attention to ethical risks (governance and ethics). It also assess whether governments have strong internal digital capacity, including the skills and practices that support its adaptability in the face of new technologies. |

| Technology | A government depends on a good supply of AI tools from the country’s technology sector, whichneeds to be mature enough to supply the government. The sector should have high innovation capacity, underpinned by a business environment that supports entrepreneurship and a good flow of R&D spending. Good levels of human capital — the skills and education of the people working in this sector — are also crucial. |

| Data & Structure | AI tools need lots of high-quality data (data availability) which, to avoid bias and error, should also be representative of the citizens in a given country (data representativeness). Finally, this data’s potential cannot be realised without the infrastructure necessary to power AI tools and deliver them to citizens. |

How are countries in the SADC region doing?

Case study: What’s Mauritius getting right?

For half a decade now – Mauritius has been regarded as Africa’s most pro-AI country. It’s not surprising given that the nation released the Mauritius Artificial Intelligence strategy document as far back as 2018 and had provisions for an AI council that far back. The strategy was detailed and proposed the country focus on the Ocean Economy, which comprises over 10% of Mauritius’ GDP. The AI strategy document suggested investment into a maritime Internet of Things.

By 2020 Mauritius’ government was embracing digital in a way most of their African counterparts simply couldn’t even dream of. The Digital Mauritius Strategy had a particular focus on cybersecurity, and the country ranked 15th in the world according to the Global Cybersecurity Index, the highest-ranking country in Sub-Saharan Africa. Mauritius had also updated data protection legislation in 2020, in order to bring it in line with the example set by Europe’s GDPR.

The government has also fostered innovation by offering tax incentives for innovative companies since 2017. The Government also grants regulatory sandbox licences to encourage experimentation and runs a National SME Incubator Scheme. In 2019, Mauritius ranked 13th in the world in the now-discontinued Ease of Doing Business rankings published by the World Bank.

All this has culminated in a small but flourishing technology sector. Port Louis can lay claim to being one of the top startup hubs in Africa, and Mauritius hosts an annual World AI Show, bringing experts and industry leaders around the world to the country to share expertise.

These efforts have also trickled down to academia. To encourage collaboration between academia and the private sector in R&D, the Mauritius Research and Innovation Council runs a scheme that offers grants for SMEs to collaborate with local academic and research institutions.

A major obstacle that exists within the region and impairs AI readiness is the “skills gap” that exists. Mauritius, however, is said to lead in this area; with Oxford Insights researchers noting the country is at the forefront regionally with regards to nurturing potential AI talent. The country has the Human Resources Development Council (HRDC), which runs an AI skills development support programme in the capital city of Port Louis. This programme introduces students ranging “from pupils to industry executives” to the fundamentals of AI; it also helps students at undergraduate and postgraduate levels with scholarships for further, specialised training in AI.

Lastly, it’s important to note that Mauritius has one of the most mature telecoms markets in Africa and government initiatives such as 350 free WiFi Hotspots and 100 Public Internet Access Points between 2015-2018 all help in fostering innovation.

Why is everyone else in the region subpar?

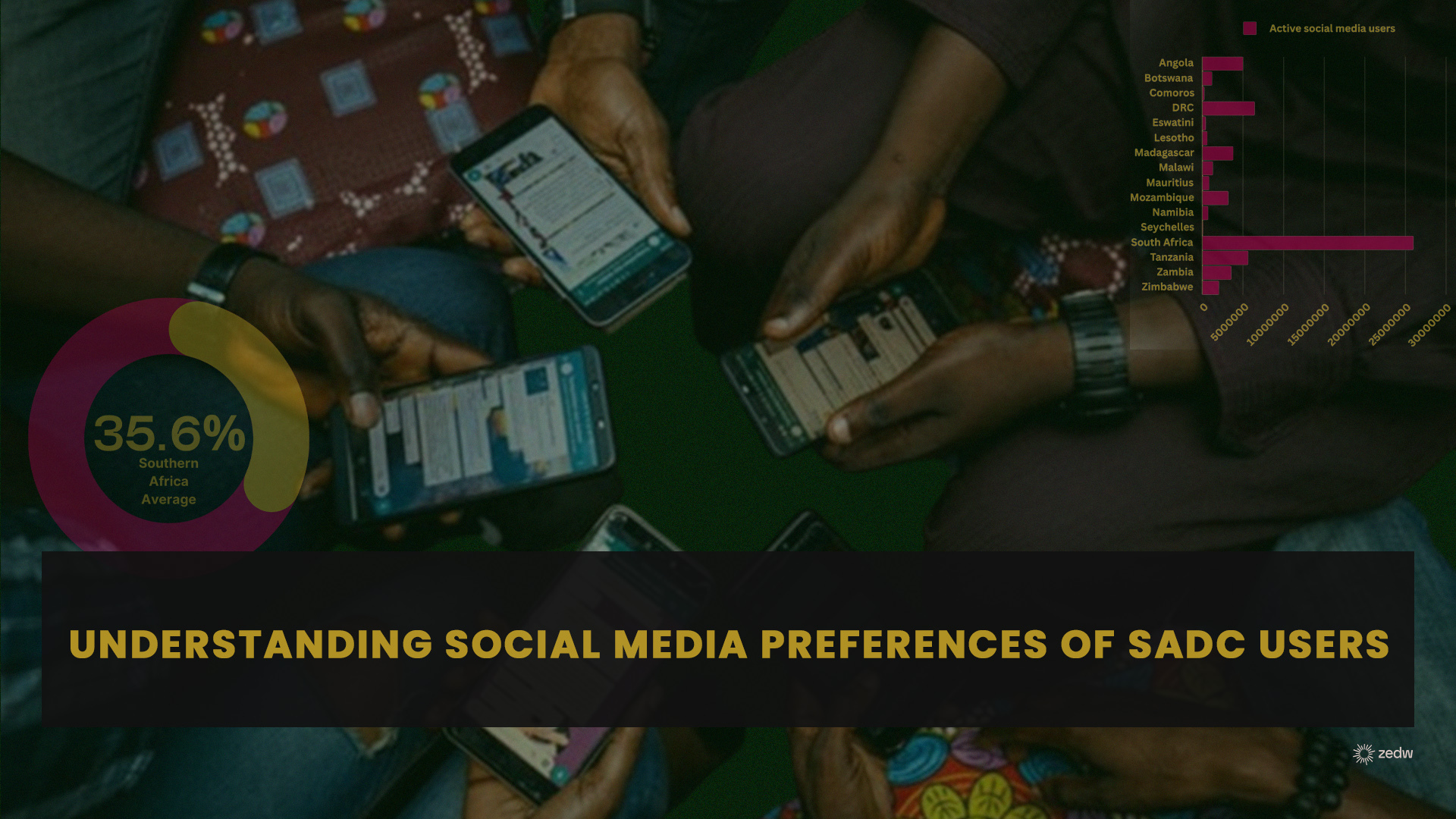

Outside of Mauritius, South Africa and Seychelles, things don’t look so great. This extends beyond the continent to the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) as only one African country has made the top 50 since 2019.

Initially (around 2019) the biggest challenge facing the characterisation of AI readiness in Africa was a lack of systematic studies around the topic. The effect of this was a lack of data and information about AI in Africa – something that’s true of many other fields. This lack of relevant data repositories covering Africa also makes it difficult to get a full picture of developments on the continent or to explain national trends. The little data that is collected in this regard tends to only focus on urban centres with little to no focus on rural areas.

Further, it doesn’t help that the region has less capacity in regards to the size of the tech sector, business environment and existence of skilled AI workers. For most of the above countries and in the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa, this has resulted in limited preparation of regulatory and ethical frameworks; and this has been coupled with governments general low use of ICTs and low responsiveness to change – all manifesting in the subpar performance within the region. There have been a few exceptions which we will get to explore in later sections.

“AI solutions don’t spring fully formed—they emerge from communities of researchers and entrepreneurs, which require a lot of groundwork to build.”

Forbes Insights

Beyond the government – Africa’s workforce also isn’t prepared to take advantage of the technology. The small talent pool that has the skills to build on AI technologies faces big constraints which include a low demand of AI solutions.

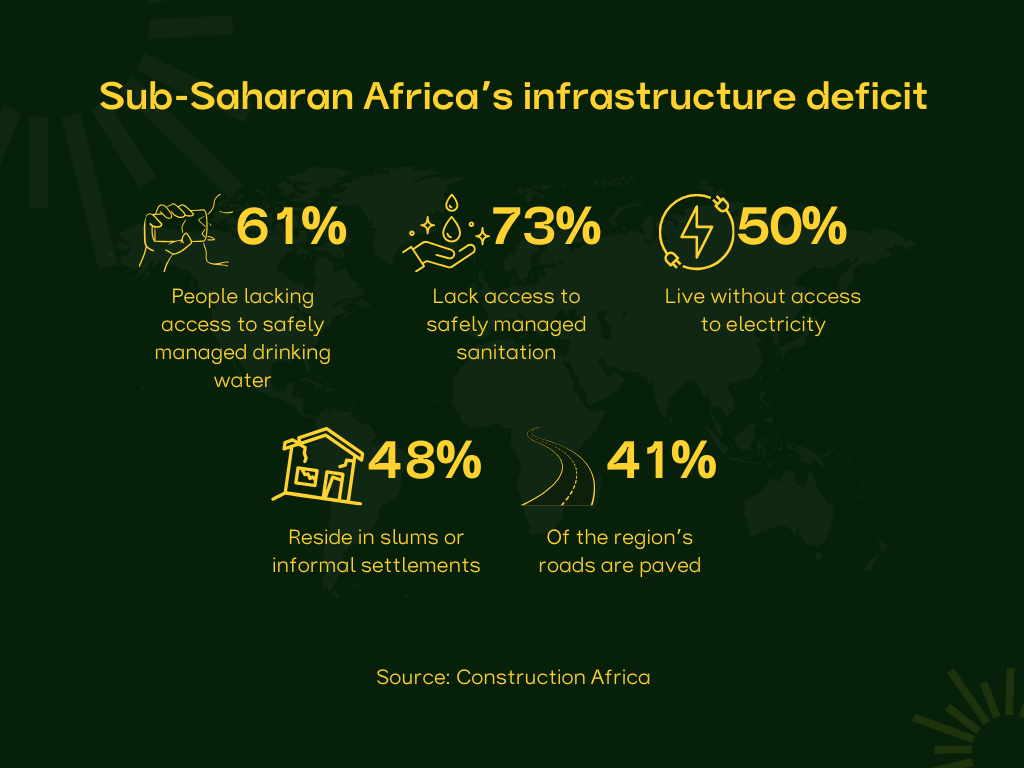

Sub-Saharan Africa ranked worst under the Data and Infrastructure pillar – with a score of 39.36 out of 100 it is significantly lower than any other region, which all score above 50. This implies a lack of core infrastructure needed to establish and support an AI ecosystem.

We’ve lamented the lack of infrastructure in Africa before and the illustration below brings to fore how hard it is for a population to focus on innovation when 50% of the SSA region (and the SADC too) have no access to electricity and an estimated 48% reside in informal settlements.

What positives are there?

It’s easy to have a gloomy outlook following the rankings and context which informs them above but there are some positives the researchers managed to establish when understanding what’s happening in the region.

The first is that since 2018 initiative has been taken to improve the state of AI readiness. Local AI labs and research centres have appeared in certain parts of Africa, such as the announcement in June 2018 that Google would open their first African AI research hub in Accra, Ghana. Other examples include the University of Lagos, which launched Nigeria’s first AI hub in June 2018 to develop the country’s AI sector and skills. Whilst this progress didn’t occur directly in the SADC region it is still beneficial at continental level as blueprints and case studies to pursue.

“Another aspect of the African tech community to watch closely is the role of SMEs and individual developers, and how they embrace AI. It remains to be seen whether AI tools are taken up by these groups and incorporated into, for example, startup companies, locally developed open source tools, and educational uses. Encouragingly, there are already numerous examples to show that AI is being applied to local problems. From sexual and reproductive health monitoring chatbots in Kenya, to smart farming in Nigeria, to the tracking of illegal fishing in West Africa by AI-powered drones, the potential for AI to aid localised technology solutions is emerging.”

Oxford Insights

Interestingly, the researchers also suspected that Africa was unlikely to feel the negative impacts of AI on employment as severely because of the nature of our workforce even if the adoption of AI is as widespread on the continent as in the rest of the world. There are a number of factors influencing this thinking – First, the largest industries in Africa still rely on high numbers of low-paid workers. The typical daily wage for a worker in agriculture or construction is less than US$10 per day. It is simply not economically practical to replace or augment such a low paid workforce until the cost of robotic labour is dramatically reduced from current levels.

Beyond this, the informal sector is substantially more important in Africa, and the impacts of AI on this sector will be minimal. Lastly, there is still relatively little R&D in AI in Africa. This means that applications of AI developed in other regions will likely lack contextual relevance, particularly in regards to cultural and infrastructural factors, and will not be fit for purpose in Africa. The feeling of researchers is that as AI and related technologies improve, many of these challenges will eventually be addressed. By the time that this happens, the African continent will be able to learn from the mistakes and successes of pioneer countries (i.e., those in the top 50 positions of the Index).

Whilst I agree with these views to a degree, I feel that a lack of AI integration might also mean that not only do we miss out on the negative outcomes brought about by the technology but we will also miss out on the positive outcomes…

We’ve established that the governments are not ready to integrate AI but that doesn’t mean everyone else isn’t either. Academia and entrepreneurs in the region have been noted for their activity – a mapping of emerging AI hotspots in the global south identified 148 players in 9 SSA countries, mostly in academia (111).

At continental level, the African Union (AU) has also taken initiative to start pushing AI adoption forward. The AU Working Group met for the first time in 2019 and aims to develop a regional approach to AI and exchange expertise between countries. Collaboration in this manner could help countries develop AI strategies, identify other regulatory and governance issues, and learn from regional best practice.

Funding has also been another thing of positive note. Between 2010-2019, Africa’s AI sector received about USD 17.5 million in government and private sector investments. Whilst the potential of the technology remains untapped there is cognisance that the tech has to be invested in – a good sign.

Another area of progress in the region is on data protection legislation, with the majority of Sub-Saharan African countries now having passed data protection laws and the African Union’s Executive Council endorsing a Data Policy Framework in early 2022

What’s next?

Now that AI is becoming hard to ignore – we’ve seen more momentum on the continent. In 2022, the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, adopted Resolution 473, a call on national governments, and the AU to work towards developing legal and ethical frameworks to govern AI and emerging technologies.

2023 saw growth again as 3 countries (Rwanda, Senegal & Benin) published new national AI strategies and one (Nigeria) announced a forthcoming strategy. In addition, 3 more countries (Côte D’Ivoire, Namibia, & Rwanda) have announced they are working with UNESCO to adopt and implement strategies in line with UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of AI.

Ultimately, whether SADC governments are prepared or not, AI is coming and they will have to reverse their trend of regression in AI readiness indicators.